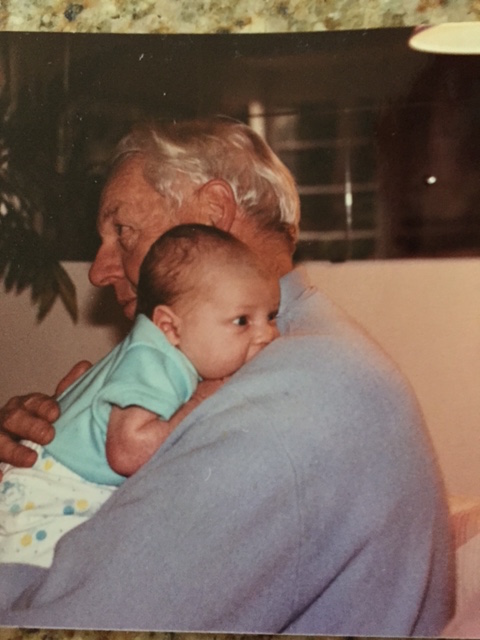

My father and my younger son, c. 1988

The telephone call came early one evening this spring. I was home alone, savoring the quiet as dusk fell. I almost didn’t pick up the phone. Too often intrusive telemarketers interrupt this hour. Then I noticed my parents’ ten-digit number, the first one I ever memorized. “Just in case you get hurt, or lost, or need a ride home, or…” The words resonated through the years with the voice of concern for their young child ever present.

My parents rarely telephone. We are letter writers. Words fly on parchment between our homes on a weekly basis. The magic and ease of telecommunication seems not to have reached them. Their telephone calls are not quite comfortable. So, on that particular, and until then, unspectacular Tuesday night, I didn’t anticipate hearing from them.

The tenor of the telephone ring seemed to portend a knowing sadness. I cautiously answered the phone. Mom’s quiet voice, calling across the miles, was hesitant. Was she waiting for the words inside her head to become perceptible? By crafting the exact words, would they take on substance and reality? Not one to ease into a conversation, the words were delivered in her typical straight-forward manner.

“Pat, your Dad has cancer.”

“Oh, Mom…”

Those initial four words were guardedly said. Only two of them had any importance, “Dad” and “cancer.” They are now, forever, for all time, inextricably coupled together. My father, invincible, ever-present, the touchstone, the paterfamilias, has cancer. It won’t matter what the outcome is. The cancer may be eradicated and annihilated. It may be made to be gone forever. Its shadow, though, will lurk always in our lives. The words, softly cried by my mother, changed in an instant our relationship. This was the call that children dread. We imagine it might come. We hope it won’t. We wonder, theoretically, of course, how we might react.

Why now? Why our father? Take the words back!

How could the linkage of these two words so quickly put such vulnerability into my parents’ lives? They strike potency almost beyond imagination. Their simplicity belies their power. Their truth imparts a new order.

All else became background noise as I tried to comprehend what my mother was saying. I strained to hear the almost inaudible words. I tried to understand the sequence of events. I strove to parse the explanation. A routine physical examination set in motion the events that brought us to this conversation. Initial tests showed a spot of cancer in Dad’s colon. More thorough exams were required. Had it spread? Would surgery be required? If so, how invasive would it be? What about chemotherapy or radiation? What was the prognosis?

Silent, heavy thoughts immediately came from deep within me, a barrage of questions: Will he survive? What will his life be like? What can we do to help? Should I visit? Do the others know? I did not even want to acknowledge the questions, let alone speak them aloud. How could I vocalize these concerns to my mother? What must she be feeling?

Mom and I talked for a few minutes. I do not remember exactly what we said. The intensity of my reaction to her initial words did not dissipate. I had a difficult time comprehending what she was saying. The words were mere sounds, really. She’d only told Janet and me the news. She wasn’t ready to tell Anne, Bruce, and Rob, my other siblings. She thought she should wait until she had more answers. She mused that letters might be sufficient. It was simply too overwhelming to listen to the heartache of each of her five children as we reacted in our individual ways to this development. Mom’s voice trailed in the distance. She could not absorb even these simple motions.

Then the familiar mantra, “I’ll let you talk to your Dad now.” How like my mother. She is the initiator of telephone calls. Dad will then say a few words. His animated voice is often lost in these long-distance forays. He strains to hear my soft voice, not catching all the words. His hearing has progressively worsened over the years, yet he refuses to give in to this gradual diminishment. That evening his words were clear as shooting stars, precious but vital. He spoke to my choked silence and flowing tears.

“I feel fine. Things will be all right. I just know it. I’m not concerned.” Then, as my breath caught once again, his reassurance: “Don’t worry. I’ll be around for you.”

Is not that just like a father? His concern is for his wife and children. He wonders how we will digest the news. He prays we will help each other. He wants to be strong for us. Yet he is the one who has the cancer. He is the one who will endure the surgery. He is the one who will undergo the chemotherapy. He will suffer the oft-times “worse than the disease” side effects. This very private man will have his condition known by all, the particulars discussed, dissected, surveyed, questioned, his body parts viewed, scanned and touched. We will be the eager, but helpless, bystanders. We will be protective of him but wanting, yet, to have him protect us.

The first few days after the fateful call passed as in slow motion. Each day was disconnected from the one before, not yet tied to the day to come. We received piecemeal bits of information. We waited for the results of each new test. We struggled with the questions we didn’t think to ask. We tolerated the anecdotes of friends and cancer survivors. Stories were told to bolster our confidence, but instead often dimmed our hope. We felt the interminable waiting, the endless unknowing, the losing control over our lives. We slowly acknowledged a nascent awareness. Our father is not immortal. He is human. He is vulnerable.

The doctor was cautiously optimistic. The cancer seemed to be contained within a small bend of the colon. Dad might live another five years or so, maybe another twenty. At that, even Mom lightened, before her quip: “I don’t think I want him around that long!” The doctor admitted that there are little statistics about this disease and its survival rate for a man in his mid-eighties. Most of the information is based on studies of younger men, those in their fifties and sixties. With this group, prognoses and courses of treatment can be more soundly made. We were incredulous when Mom relayed these comments to us. Like the linkage of cancer with our father, we did not comprehend our father in the context of being elderly. How could that be?

We have seen our friends’ parents and grandparents age. Their movements become slower as their limbs stiffen with inactivity. Their eyes cloud as the luster of younger years fades. Their words are haltingly spoken, as if the synapses between brain and speech have lost their way. Their beings gradually diminish. Certainly, my parents are no longer as robust or smooth skinned as they once were. Their hair has turned white. They are less supple in their movements. Their opinions are stronger, more entrenched. They don’t like to drive at night. Indeed, they’ve made some accommodation for their age, but really, just the inconsequential things.

When I look at this man and woman, I only see my parents—strong in spirit and self. I hear the vitality and enthusiasm in my father’s voice. I reflect on their concern for one another, their astute knowledge of the world, their passionate involvement in life and their endless traveling. I do not see them wearing the mantle of their chronological age. I do not see a feeble old man and his tottering wife. I look at myself and do not see a grown daughter. Do others?

Recently, though, I have heard in my father’s voice, sometimes unspoken, other times frankly admitted, of his concern for our mother. He sees her slowing, her forgetting the little things of a few minutes before, her becoming less independent and strong, her losing patience over an insignificant slight. He will then laughingly, but lovingly, comment on what a bear she will be when she is old! He will take care of her. He feels daily their commitment of more than fifty years ago. He will not break that promise, even as he faces a devastating illness. Yet, he worries of the time when he will be gone.

My father does not want our mother to grieve, too much, his passing. Their shared life has been more than he would ever have imagined in joy, love and friendship. One day, they will of necessity depart. We have the papers certifying the “do not provide extraordinary treatment” orders. We have visited the cemetery where their remains will be placed, among rows of friends in the mausoleum. We know of their plans that comprise growing closer to death. We have accepted the inevitability of their decisions. In truth, they have made it easy for us to do so. They refuse to be a burden upon us. Until now, these conversations, the planning and the decisions have had a contemplative tone. Perhaps sometime in the future (or maybe, never), certain actions will be necessary. Now, we are hit squarely with the future. What decisions are we facing?

But of course, the doctor is right. His patient is eighty-five years old. Dad has long since passed the average mortality rate of a male born in 1916. We are told that Dad’s cardio-vascular system is as strong as a forty-year old man’s. We rejoiced, “See, we knew it would be all right.” Then, “But still, he has eighty-five-year old organs. The chemotherapy can devastate the organs. That is where we must be concerned.” We are deflated. The roller-coaster ride has begun and we did not choose to purchase a ticket.

There is no escaping the facts. For all his optimism, his athleticism, his good health, his endearing spirit, our father has cancer and he is old. His disease must be treated within the confines of this knowledge. The doctors are at a loss for how to measure what is not measurable. They do not know how to answer that which has no right answers. “We just don’t know.”

The ever-presence in my life of the consequences of having elderly parents permeates my daily travails. It colors my interactions with others. It touches my very soul. When did my parents become elderly? When did their lives become so delicate? When did they start to diminish? Why didn’t we see it? If we had, would we be better prepared now?

No matter, now. I did not see it happening. I did not feel it in my bones. I cannot still admit their fragility or their mortality. I do not want their time on this earth to be any less than it once was. I do not want things to change so drastically. I wish they were younger. But still, “Your father has cancer,” rings in my ears.

I want to continue my “walks and talks” with my father. This man’s wisdom and humility provide me warmth, fellowship and strength. I do not want him to have cancer. I do not want him to suffer. I did not want this to happen. I have known and loved my father longer than anyone else, save my mother. How can I express to this man of my deep sorrow for him? How do I grieve for what I may no longer have? Who will take his place?

Janet was home during the surgery. She reported that Dad was ashen. He appeared swallowed and shrunken by the whiteness of the hospital bed. He looked like an old man. An emergency second surgery had taken a heavy toll on our parents. Our mother was weak and shaken by the recent events, unable to cope with even simple tasks.

My sister carefully choreographed our visits home. We did not want Mom to be left alone. Each of us made the trek home to provide solace and support. We have also gone, I think, to obtain the familiar reassurance. We are still the children and they are still our parents. The long-established historical roles are still intact. The binding ties are critical to our existence. It forms who we are, who we hope to become, why we wake in the morning.

My childhood home.

When it was my turn to visit, I arrived at the house late. I did not know whether Dad had been released from the hospital. I quietly walked up the steps into the darkened house, all the lights off except for a soft glow in the living room. I tried to gather my courage. I had taken Janet’s words literally, enhancing them in my mind’s eye, imagining the worse.

I was afraid of visiting. I truly did not know what to expect. Would Dad be gaunt and listless? Would Mom be less steady, pale and thin? No matter the telephone calls, the descriptions of Dad’s progress or the daily updates. I needed to see and touch my parents. I needed to know for myself that they were all right.

Mom’s note was on the kitchen table: “Dad is home! He is upstairs in his bed!” The chicken-scratched scrawl was recognizable as ever. I could feel her joy simply from reading those few words. I crept up the narrow stairway to my parent’s bedroom. As I peeked around the stairwell, I heard heavy, labored breathing. Dad was curled, asleep, under his heavy quilt in their room. Mom was laying flat with arms straight by her sides, her mouth slightly agape, in the narrow twin bed of the guest room. Their relieved sleep permeated the house. All was serene. This night’s rest was their elixir. They were together in their home. There would be time to talk tomorrow.

I tried to sleep in my childhood bed. About 2 a.m., the sound of people talking interrupted my fitful dozing. I followed the steady noise to its source, carefully feeling my way through the still house. And then I saw him. Dad was in the brightly lit family room. He was sitting in his old red-leather chaise lounge. He was wrapped in his multi-colored, now worn and tattered, bathrobe. He was drinking tea and watching a nondescript movie. My heart leaped to my throat. My mouth broke into a huge smile. My eyes started to water as I slowly approached him.

The man facing me was the father I remembered. His smile pulled me into his heart. His proverbial twinkling eyes captured my soul. His words of welcome were simply said. My fears and apprehension dissipated.

Yes, my father’s hair is white. His face has softened. His frame is stooped. He is elderly. None of that matters, though. I gingerly hugged him, hungrily drinking in his image. I wanted to curl up beside him, aching to tell him everything would be all right. I was home.