Mission Bay, Auckland, New Zealand

A collage of images floats through my mind: me as a ten-year-old, slightly-chubby girl, tent camping in the rustic wilderness (no toilet, no running water, no electricity), homemade gauze net in hand, waiting for the night’s dew to dry, breathlessly anticipating the flitting of yellow and blue butterflies, a growing self-confidence away from the eyes of my school mates. In my early twenties, a startled yelp and then laughter as I dipped my aching, tired feet in the icy-cold water of the glacier-fed lake, after hiking miles up narrow, steep trails, my backpack weighted from pots and pans, fishing gear, and books. As a hesitant new mother, tightly-clutching my wide-eyed six-week-old beautiful baby boy, alone in the sun-filtered grove of trees, the stress of the recent months falling away, if only momentarily, after the breaking apart of my marriage. No matter the season, the geography, or the circumstances of my life, there is a thread, sometimes straight, other times twisted, connecting my state of mind and physical well-being after time in the forests and woods.

What is it that propels me to forests, to trees? How do I explain the feelings of joy engendered running along the Avenue of the Giants under the canopies of the huge Redwood trees; or the awe from watching the Biloba Gingko tree outside my apartment window drop all its leaves simultaneously after near-freezing temperatures; or the trust in myself after scrambling up the gully of scree and loose granite high above the Mountain Hemlock and Western White Pine forests of the Sierra Nevada mountains, to reach the 11,500’ peak of Mt. Vogelsang?

Lake Vogelsang, High Sierra Mountains, California.

I wonder at the changes that could be happening in me, psychologically and physically, beyond what I see or feel when I’m in forests. Is there something in my cells that causes or evokes these feelings of comfort and solace, joy, energy, even confidence? I am not alone in this wondering. Nature lovers for centuries have experienced the positive effects of being in the woods. My book shelves are filled with the works of men and women who value the benefits of nature and who fear for their loss. Henry David Thoreau believed that we can only understand life if we have an understanding of nature, living his philosophy in a small cabin at Walden Pond for over two years. Mark Twain journeyed from New York to Bermuda to “…[put] distance between ourselves and the mails and telegraphs.” There, he and his companion explored the island, “…through stretches of forest that lie in a deep hush sometimes, and sometimes are alive with the music of birds;” walking aimlessly and without purpose, “…in maiden meditation, fancy free, by field and farm…” John Muir, one of our most beloved naturalists, described American forests as almost religious, with their trees “—lordly monarchs proclaiming the gospel of beauty like apostles.”

Recent physiological and psychological studies are putting hard science behind the importance of the natural world to our physical and mental well-being. They may help explain the magic many of us feel when we’re in forests, too.

***

Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines “forest” as (1) a dense growth of trees and underbrush covering a large tract; (2) a tract of wooded land in England formerly owned by the sovereign and used for game. The definition doesn’t begin to describe the immensity, the variety, the diversity, the age, or the liveliness of forests. Some forests may be one organism, e.g., the Pando Aspen Grove in Utah, estimated to be 80,000 to one million years old, is believed to be one clonal colony of a male Aspen tree with a massive root system. Other forests are extremely ancient, home to thousands of species of insects, animals, and birds; at one time dinosaurs may have roamed in them. The two million-year-old Kakemega Forest in Kenya, once part of the Guinea-Congolian Forest, was a tropical, lowland rainforest that covered much of the Congo Basin region in northern Africa. In Malaysia, the 130-million-year-old Taman Negara forest, one of the world’s oldest deciduous rainforests, covers parts of three countries. The 55-million-year-old Amazon Rainforest is more-known for its massive deforestation due to clearing and burning for domestic farming and agriculture than for its rich history of indigenous people and exploration and abundance of life.

Ficus Tree, Auckland, New Zealand

In these very old forests, I imagine densely packed trees, straight and tall, reaching to the bits of sunlight filtering through their uppermost leaves; the understory soft, covered in leaves, fungi, exposed bulky tree roots, and tangled lower branches; streams and rivers crisscrossing the land, moist and squishy; intense greens of every shade possible. I hear the high melody of songbirds, the deep squawk of scavenger birds, the echo call of mating birds. I smell the musty, dank odor of decay, the life cycle of the forests’ flora and fauna. I am merely a tiny speck in these massive living, breathing, growing organisms.

My imagining became reality after spending several weeks in an urban neighborhood apartment in Taipei with my son and his family. The streets were frenetic, filled with puttering scooters, darting bicycles, and bobbing umbrellas. The greys of the buildings blended into the damp skies, leaving an impression of flatness, no horizon. In the early mornings, I walked the narrow streets to Daan Park, a small oasis of green beneath rumbling concrete highways and across from sharp-cornered, ubiquitous buildings. I ran in loops around the park’s perimeter while Taiwanese elders practiced Tai Chai, played croquet or merely walked in the misty morning air. In the middle of a dense, cacophonous, almost claustrophobic city, this simple time in a small city park calmed me, preparing me for the days ahead.

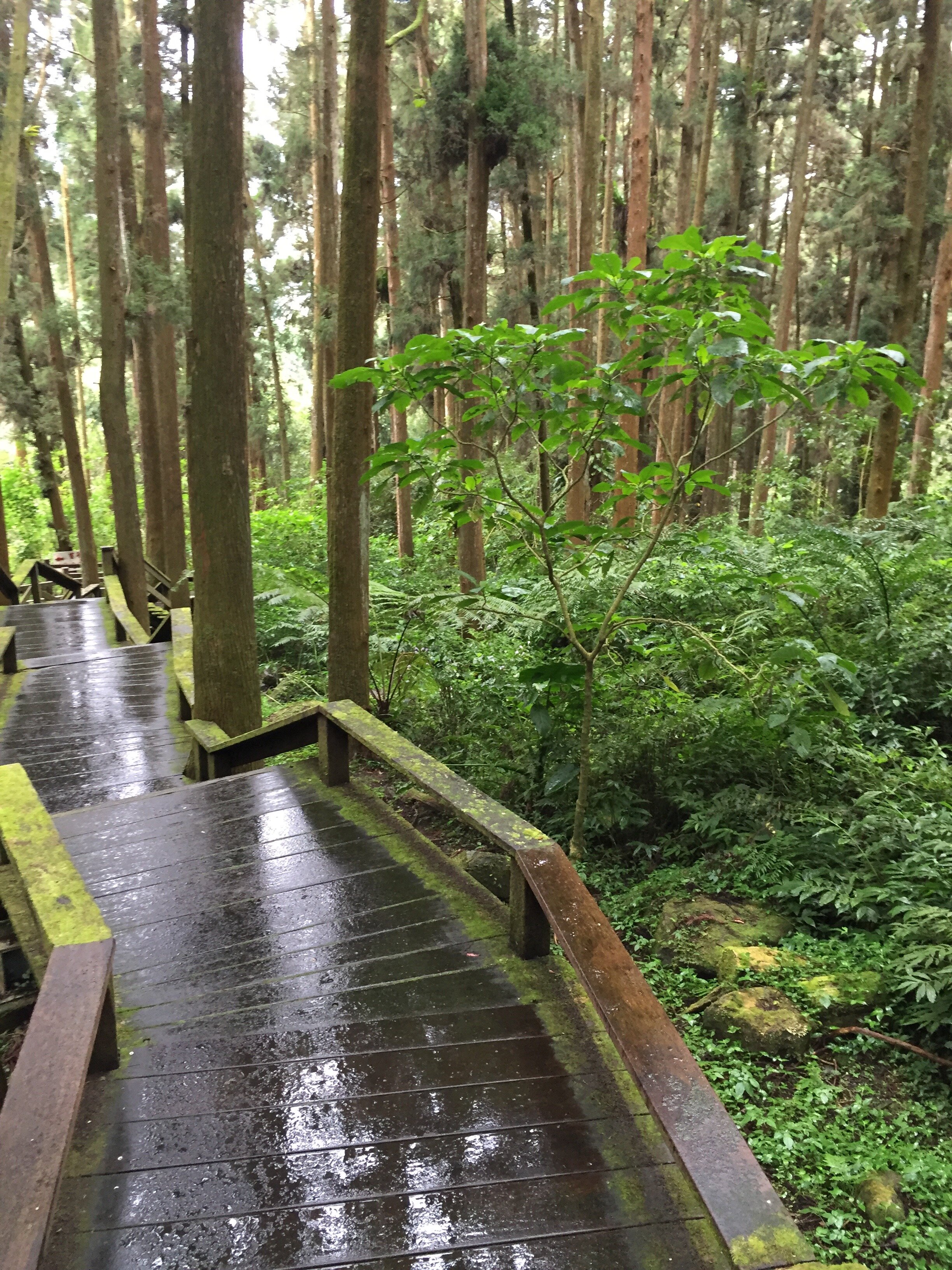

Walkway in Alishan Forest Recreation Area, Taiwan.

One weekend, we drove to Alishan Forest Recreation Area (an area originally settled by a Taiwanese aborigine tribe in the 1600s) to escape the city. High in the southern mountains of Taiwan, tourists crowd to see the cherry blossoms in Spring. Yet on a late chilly January afternoon, the wooden plank walkways protecting the prolific ferns beneath our feet were almost barren of visitors. We slowly walked on soft needle-covered pathways, the smells of damp Spruce and sweet Pine tickling our noses, the moss-covered, striated bark of huge 2,000-year-old Formosan Cypress trees rough against our hands. These gigantic trees were among the few left-over after intense logging during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan in the early twentieth century. Our faces relaxed, our shoulders loosened, our feet almost skipped, our minds far away from the city. The tension of the harrowing drive melted away as we savored the shushing stillness of this ancient forest.

***

According to Japanese and South Korean studies on shinrin yoku, or “forest bathing,” the practice of spending time in the forests—which we definitely were doing our time in Alishan—what I may have been feeling were my own cortisol levels dropping. “The idea is simple: if a person simply visits a natural area and walks in a relaxed way there are calming, rejuvenating and restorative benefits to be achieved.” The proponents of forest bathing report both good health and psychological well-being for those who “take in the forest atmosphere.”

Some of the physiological effects of forest bathing include lower levels of cortisol (the body’s main stress hormone, which regulates a wide range of processes, including metabolism and immune levels), lower pulse rate, lower blood pressure, greater parasympathetic nerve activity (prepares body for intense physical activity, the “fight or flight” response), and lower sympathetic nerve activity (relaxes the body and inhibits or slows many high energy functions). Evergreen trees, in particular, emit antimicrobial, volatile aromatic compounds called phytoncides into the forest atmosphere (think about the sweet vanilla smell of Ponderosa Pine trees), which may contribute to the lowering of cortisol levels and other health benefits.

While many of these physiological effects can be felt, research suggests that the emission of phytoncides and their impact on lowering cortisol levels may enhance the body’s natural killer (“NK”) cell activity, the number of NK cells, and the intracellular anti-cancer proteins in lymphocytes. The NK cells are a type of lymphocyte (white blood cell) and a component of the immune system. They play a major role in the host-rejection of tumors and virally infected cells. While I’m not ready to cancel my annual breast and skin cancer screenings, I’m excited about the potential use of natural phytoncides as a chemotherapeutic agent for treating tumors.

The early studies of the physiological effects of being surrounded by forests were primarily based on tests conducted on very small samples; until broader testing with control groups is undertaken, the results merely “suggest” that forest environments have the above-enumerated beneficial effects. Yet they all point to a calming effect, providing the body a break from the chaos and high-level stresses of daily life today.

The psychological outcomes of being in natural environments have a more sound evidentiary base. One study found that stress (especially chronic stress) and depression decreased significantly in a group of volunteers after walking and/or staying in forests compared to being in an urban setting. Shinrin yoku may be a factor in improving mood, increasing the ability to focus, especially in children, and increasing energy. A comprehensive 2019 review of eight years of research into psycho-physiological stress recovery found that outdoor, nature-based exposure has a positive effect on different emotional parameters related to stress relief.

A number of organizations actively promote walks in the forest, advocate for the development of green or blue spaces in urban areas, train forest and nature therapy guides, even prescribe time in nature for stress or depression. They advocate the reduced stress levels, increased feelings of calm, and heightened moods after time spent in nature, even as little as two hours a week. A group in England touts the benefits of forest bathing and encourages forest therapy walks; another organization trains and certifies forest guides to teach and guide people on forest walks; while a U.S.-based group measures how many urban areas have green spaces within ten-minutes walking distance of their residents’ homes (a distance that seems likely to allow people easy access to them), and promotes the development of more green space in environments where access is limited.

Reflexology walk, Daan Park, Taipei, Taiwan.

The authors of a 2019 study compiled the results of hundreds of research studies and theories to more systematically understand the value of nature experience to our mental health (or quality of life). The variables are significant when determining what IS nature experience: an individual’s perceptions and/or interactions with the natural world, sensory modalities, “real” (in situ) contact with nature versus simulations, deliberate or intentional exposure to nature, and the diverse activities with which one can engage with nature. There are numerous barriers to accessing nature, whether structural or personal (maybe someone does not like or is afraid of being in nature; maybe she lives in an inner-city where access to green space is extremely limited or transportation to forests difficult or expensive; maybe he has had a disability that limits mobility; maybe their economic circumstances do not allow the luxury of hiking in the woods or driving to the nearest lake or ocean for the day). While beyond the scope of this article, the authors describe a variety of interacting factors that can affect mental health in addition to spending time in nature, including social, economic, psychological, behavioral, environmental, genetic, and epigenetic influences.

What is pertinent to the growing practice of immersing ourselves in nature are the controlled studies and experimental fieldwork, cross-sectional, and longitudinal studies that have shown positive effects, both correlational and causal, of nature to mental health. This consensus gleaned three key points: an association between common types of nature experience and increased psychological well-being (e.g., increased positive affect, happiness and subjective well-being, positive social interactions, a sense of meaning and purpose, and decreases in mental distress); an association between common types of nature experience and a reduction of risk factors and the burden of some types of mental illness (e.g., improved sleep and reductions in stress, which may be factors in reduced depression, and decreased incidence of other disorders, e.g., anxiety, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, and depression); and that opportunities for nature experience are decreasing in quantity and quality for many people around the globe (e.g., due to increased urbanization, increased time spent indoors, on screens, and in sedentary activities, and a narrowing of accessible nature experiences). These findings will be critical to include in making well-informed decisions about the environment, e.g., by city planners, developers, environmental activists, and health professionals, that may also impact our mental health.

***

Looking west toward Indian Peaks Wilderness from Brainard Lake.

August 5, 2014: The car almost drove itself up Boulder Canyon, my mind distracted from the early morning call, the one none of us wants to receive, the one informing us that a parent has died. I barely noticed the two-lane windy road within the steep canyon walls, the snow-covered sharp peaks of the Rocky Mountains in the distance, the spruce trees lining the creek bent from the previous year’s ravishing floods. But as soon as I left the car at the trailhead and entered the wooded Indian Peaks Wilderness Area, my body responded to the familiar trail, my legs full-stride, stepping over rocks and exposed tree root, skirting around the pond-filled meadow to the left before pausing at Mitchell Lake, shimmering in the sunlight, to the right.

All my senses were engaged, the August day in bright technicolor. The light-green of the Aspens quaking in the light breeze, their leaves shimmering in the sunlight, giving way to the darker, more severe Lodgepole Pines as I gained elevation. The water breaking and bubbling over rocks murmured and whispered to me. The area was replete with wildflowers: Colorado Blue Columbine with its blue-and-white star-shaped flower; Indian Paintbrush, red and orange atop tall stems; familiar Bluebell, shaped exactly as its name suggests; Silky Lupine, tall stalks with bluish, oval-shaped flowers. I spotted a few birds, likely hawks, circling for prey. The stillness was powerful, vivid memories of my curious, smart, opinionated mother tumbling one after another in my mind. Tears flowed, but a smile emerged as I sat on a boulder, the noon-day sun burning into my bones. My mother would have wanted me to spend this day of all days in my beloved forests.

Brainard Lake, Indian Peaks Wilderness, Colorado

The occasion of the hike was sad, but the forest caressed and comforted me. A lightness lingered as I later dealt with both the mundane and the immense issues of my mother’s death. The science may still be in its infancy, but the forest bathers and the mental health advocates have found something irrefutable and undeniable. This was my parents’ legacy, something they instilled in me at a very young age: the simple act of being in the forest provides us endless opportunities for joy, peace, calm, and sustenance.