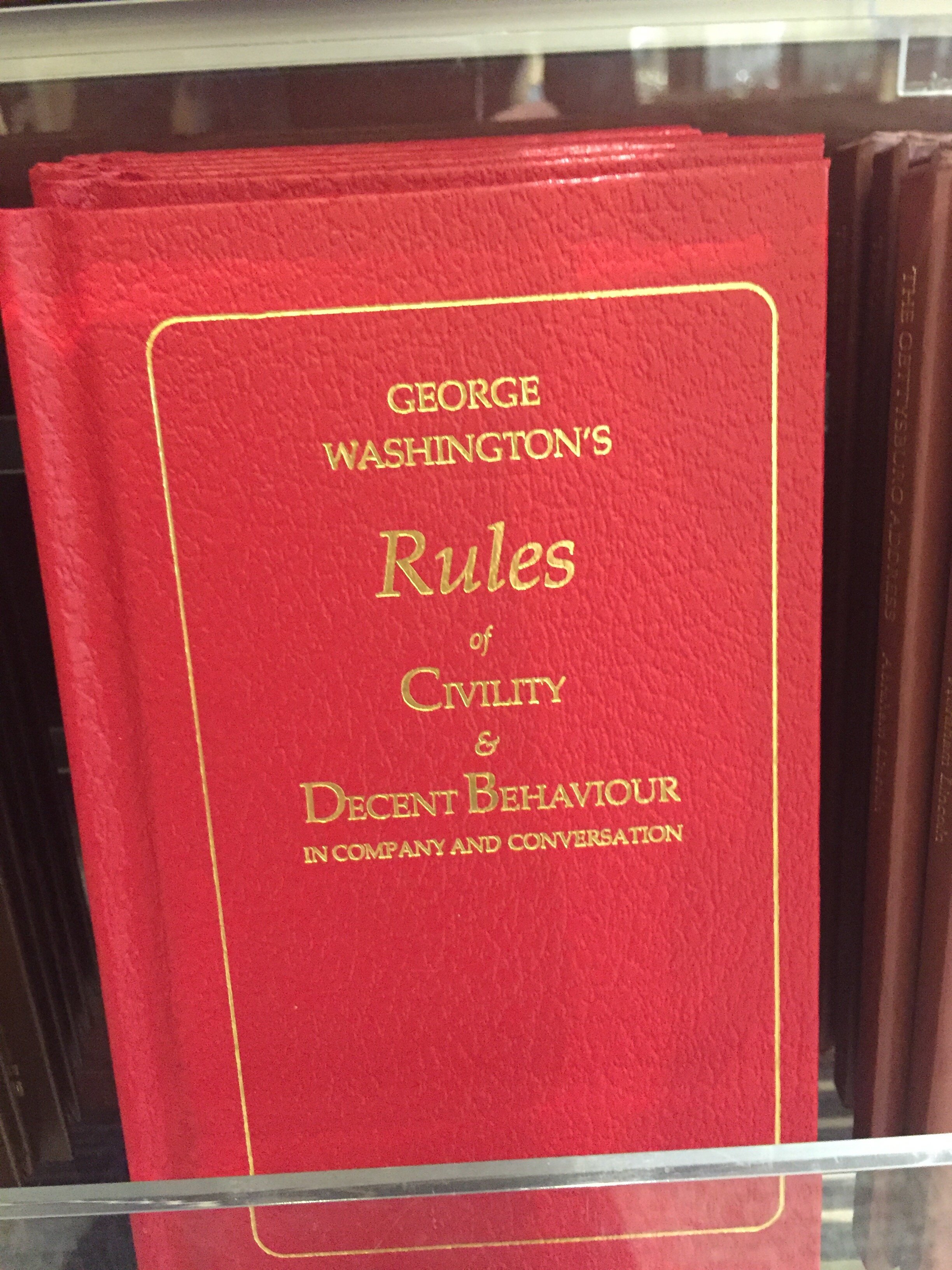

Library of Congress, best seller?

This year should have been ideal for reading. We stayed at home. We were isolated. Books were readily delivered by independent books stores and Amazon. Most in-person events were shuttered. My never-ending pile of books provided a visual, daily reminder of possible selections. I had time, at least theoretically, compared to prior years when my calendar was full of daily commitments and events. I imagined I’d be reading a book—or more—a week. Yet at times, I almost couldn’t read, the underlying malaise over the uncertainty of the pandemic and the concomitant economic, social, and health disruptions, a feeling of lack of control over what we could and could not do, the repetitive sameness to each day, combined to distract me from any ability to focus. In fact, I read fewer books this year than in prior years, even though quality over quantity is what I aspire in my reading.

With that backdrop, I noticed several patterns in this year’s list of books read: works of history and historical fiction were heavily represented, often slower reads as I consider and ponder what was then compared to what is now; a number of books were long, almost lumbering; several were so beautifully written that I savored the words, quietly, slowly; a trilogy and part of an quartet, which carry the decision whether to read all the books in each series, entered my lexicon; books about nature, detailed and sometimes sonorous, percolated to the top of the list; and even a book about goddesses, witches, and sorcerers grabbed my attention. My choice of books continues to be eclectic and the act of reading remains necessary to me.

Here’s a summary of the books I read this year, with the starred (*) ones within each genre or self-described category among my favorites.

NONFICTION

History

*Leadership: In Turbulent Times, by Doris Kearns Goodwin. What attributes define a great leader: are leaders born or made; how do some leaders learn from difficult, heart-wrenching personal grief or despair into men and women who develop the deep strength of character to act selflessly and make difficult decisions; how do leaders evolve from personal ambition to the most important element of leadership, empathy; how do leaders gain the trust of the people whose lives depend on their insight and foresight; and how do the events happening during times of leadership influence or impair a leader’s ability to lead? This book emphasizes to me how critical it is to have leaders with vision, strength of character, humility, integrity and empathy to lead us forward in our turbulent time. Before the Mayflower: A History of the Negro in America 1619-1962, by Leone Bennett, Jr. A sentinel history of African Americans, commencing with their African past, their movement to the Americas, whether voluntarily or involuntarily, the Civil War, the Reconstruction era, Jim Crow, World Wars I and II, their migration from the south to the north and west, the consequences of segregation, and a study of their great leaders. *Tightrope, Americans Reaching for Hope, by Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn. An analysis, through personal stories and failing national policies, of the causes of poverty, increased suicide and opioid rates, rising unemployment (and the despair of no employment), lower high school graduation rates, and the consequences of mass incarceration throughout our country, but particularly in rural areas.

Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister, Three Women at the Heart of Twentieth Century China, by Jung Chang. The story of the three Soong sisters: Ei-ling (oldest sister) who was one of the richest women in China, and advisor to Chiang Kai-shek; May-ling (little sister), who married to Chiang Kai-shek who became the “First Lady” of China, and then, with the Nationalist Party in Taiwan; and Ching-ling (Red sister) who married Sun Yat-Sen, and was vice chairman of Mao’s China. The book covers a significant period in China, from the first revolutions through the downfall of Mao’s Cultural Revolution. *Wanderlust, a History of Walking by Rebecca Solnit. An exploration of walking from a means of getting from one place to another, to its use as a tool to spark the imagination of poets and writers, to pilgrimages to religious sites, the promenades, parades, revolutions, insurrections, processionals and marks of protest on public streets; the access to and closure of open spaces in rural areas. The Library Book, by Susan Orlean. The investigation into the 1986 fire of the LA Central Library that destroyed almost a million books becomes an ode to libraries as public, inclusive spaces; book repositories along with services such as information gathering/sharing, community gatherings, and public service (e.g., classes, story time for children, literacy programs, internet access, social services programs, a place for the homeless). The Last Castle, the Epic Story of Love, Loss, and American Loyalty in the Nation’s Largest Home, by Denise Kiernan. A detailed history of George Vanderbilt and his family, with focus on the Biltmore Estate, a 175,000 square foot mansion, situated on tens of thousands of acres of forests in Asheville, NC.

A walk in the Woods, Nederland, Colorado

Nature

*The Songs of Trees, Stories from Nature’s Great Connectors, by David George Haskell. A lyrical book about twelve trees, in urban, Amazonian, boral, coastal or war zone settings, studied over a number of years to explore their relationships with the world around them. The life of trees is a metaphor for the life of the planet, as all are affect be evolution, climate effects, Israeli-Palestinian conflict, fire destruction, ocean erosion of beaches and habitats, archaeology, cityscapes. *The Tree Where Man was Born, by Peter Matthiessen. Journalistic observations of several trips to East Africa in the 1960s, including the history, anthropology, ecology, geography, changing ways of life, wildlife, and cultures. While political divisions, civil strife and wars, modernization, over-populations, immigration, etc., have changed the story of East Africa, it is still a land of contradictions, incredible beauty, drought and floods, stories, and heartache. The Language of Butterflies, by Wendy Williams. Butterflies are colorful, intelligent insects, living remarkable lives, especially Monarchs, who may migrate thousands of miles each year. “Butterflies unit us across generations and across space and time. They are elemental.” Why We Run, a Natural History, by Bernd Heinrich. The author’s story of becoming ultrarunner, and his trials with nutrition, training programs, advice, and self-motivation is interwoven with an anthropological study about why and how humans evolved, their early days as hunters-gatherers, along with a comparison/contradiction to other species. Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion, by Mark Twain. Musings about a journey to Bermuda from New York City for the purpose of “putting distance between ourselves and the mails and telegraphs.” In Bermuda, he and his companion explored the island, marveling at the coral white buildings, the meandering roads, the friendliness of the small community. Mozart’s Starling, by Lyanda Lynn Haupt. The author uses Mozart relationship to a pet starling, one of the world’s most reviled birds, to explore the broader concepts of “other-than-human” experiences, musicology (Do birds make music?), linguistics (What makes human language distinct from other animals?), bird sound patterns (Why do some birds learn a set of sounds in early life while others learn and change throughout their lives?), and “music of the spheres” (Is there language or common sound among different species, the earth, the planets?).

Social Science

Imagining a Great Republic: Political Novels and the Idea of America, by Thomas E. Cronin. The author categorizes about forty American novels to describe different political ideas and ideologies that course throughout American history in the telling of the “idea” of America. Thinking, Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman. A groundbreaking tour of the mind, explaining the two systems that drive the way we think. System 1 is fast, intuitive, and emotional; System 2 is slower, more deliberative, and more logical. Kahneman exposes the extraordinary capabilities, and the faults and biases of fast thinking, and reveals the pervasive influence of intuitive impressions on our thoughts and behavior.

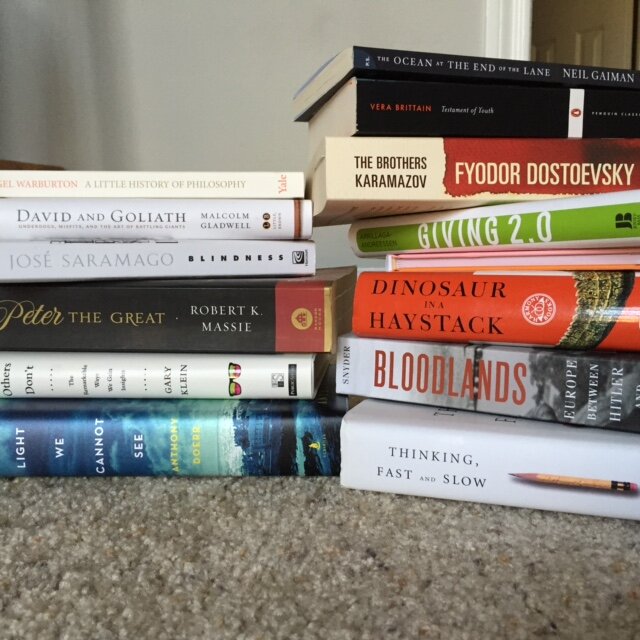

Always a pile of books to read

Memoir

*Rough Ideas, by Stephen Hough. Musings about music, performing, musical scores, musicians, the minute details of learning to play and practice, how to live as a professional pianist. Bad Feminist, by Roxane Gay. A series of essays about “not a feminist,” friendships, women, work, race, the mundane pieces of life, told in a self-effacing way with wit, humor and depth. The Fixed Stars, by Molly Wizenberg. The author seeks to understand who she is, her essence, her being, whether gender, sexual orientation, roles as mother, wife, then ex-wife, girlfriend. Urging others to question who we are, why we behave the way we do and to turn over assumptions, to step outside comfort zones.

FICTION

Historical Fiction

*Hamnet, by Maggie O’Farrell. This historical fiction is at the top of this year’s list. It is magical and sad, linking the death of William Shakespeare and Agnes (Anne) Hathaway’s eleven-year-old son, Hamnet (twin to Judith), with Shakespeare’s writing of the tragedy, “Hamlet.” The absent father, in London writing and performing plays, is almost a secondary character while Agnes, the mother, deftly created from the few historical facts in existence, is the center of her family and the book. The essence of this book is how does one survive the death of a child? O’Farrell’s writing is rich, moving, sorrowful, bringing the reader into the heart of Agnes and her family. *Barkskins, by Annie Proulx. This historical novel covers three hundred years, beginning in the 1690s in New France (Canada) and the United States, following two European immigrants and their families who came to the American continent to find a new life, riches, and escape. While the characters are fictional, the history of the massive destruction of the vast forests (believed to be infinite), the skirmishes, the devastation of flora and fauna, the misunderstandings among the various populations, the hard living conditions, the annihilation of Indigenous people, forest destruction, and heartless greed, form a backdrop to the recent reforestation movement, climate change, and the consequences of unchecked development.

*The Glass Palace, by Amitov Ghosh. Set in Burma, Bengal, India and Malaya beginning in mid-1880s, this sweeping story covers the colonization of these countries, the deposition of the Burmese King, Burma’s development of wood and rubber exports, the invasion by the Japanese during World War II through the 1990s and imprisonment of Aung San Suu Kyi, its first democratic leader. The Alice Network, by Kate Quinn. The Alice Network dives into the British women spies during World War I (with some continuation during WWII), revealing a little known but critical part of the Allies’ effort during the wars. *The Island of Sea Women, by Lisa See. The haeyneo (women sea divers) of Jeju Island, Korea, are the primary breadwinners in their matrifocal society. The book is rich with tales of the amazing discipline and strength required to dive day after day in harsh conditions, along with incredible hardships, betrayals, misunderstandings, the horrors of war and foreign occupations, the extreme poverty, and the beauty of friendship. Guests on Earth, by Lee Smith. Based on Highland Hospital in Asheville, NC, mental hospital in 1930s-1940s and the patients and treatments of the era. What is home, what binds us together, how do we create community and friends? The mentally ill, described as “guests on earth” during their life, a line by F. Scott Fitzgerald), the story melds the line between who is sane and who is not. Alaska, by James Michener. The epic (and very long) story of the birth of Alaska from its geological formations to statehood and the discovery of oil. He takes us from the early Russians, struggling across the Bering Sea for fur, to the Indigenous peoples, living harsh, almost unbearable lives in the ice and cold, the dark of winter, and the brightness of summer, the clashes of cultures, the gold-seekers, the thieves of every nationality, the tale of Seward’s purchase and America’s lax approach to this unknown, huge, harsh, icy land. The ending a question: what will/has Alaska become? A Long Petal of the Sea, by Isabel Allende. The story of a Catalan’s family’s struggles in Barcelona, Spain near the end of the Spanish Civil War, then as refugees to Chile. What it means to be refugee, how to find hope, compassion, friendship, along with history of both Spain and Chile’s civil strife. The Givers of Stars, by Jo Jo Moyes. The Packhorse librarians (established by WPA and operational from 1935-1943), were women who rode throughout the rugged mountains of the southeast to bring free library books to rural residents. It is also a narrative of the lack of women’s rights, subjugated to the whims and direction (and often abuse) of their fathers and husbands, given little freedom to be “different” from social mores and expectations, and the segregation of blacks.

Bow Bridge, Central Park, NYC

Books about Disappearing or Absence (not a genre but a key element in several books read)

*Reservoir 13, by Jon McGregor. Another favorite, the primary character of this novel is a small community in the English moors. A thirteen-year-old girl goes missing and while the entire town searches for her, she is not found. Yet, over the next thirteen years (the novel’s duration), the idea of her and each resident’s response remains rooted in their lives. The seasons change, the flowers and birds and animals live and die, the residents grow up, leave home, marry, divorce, return home. The time is measured by daylight and night fall, by the shortening days of winter, the filling days of summer, the cycle of life. 1Q84, by Haruki Marukami. This monumental work (1300 pages!) is, at its essence, a love story: two lonely ten-year-olds friends hold hands and twenty years later, they are at the center of a separate, alternate world, the year “1Q84,” full of intrigue, two moons, religious cults, assassinations, mysterious disappearances. The story is compelling and complex, drawing me in at each new twist, the separate chapters focused on a particular character as a way to keep track of what is happening. A Book of Common Prayer, by Joan Didion. An urban mother ends up in small, third-world Central American country, trying to find her 18-year-old terrorist daughter, sought by the FBI. The “atomization of society” is the 1960s-1970s is backdrop for Didion’s writings. Her characters are spare, without visible drama, unable or unwilling to see the consequences of their actions or inactions.

Divisadero, by Michael Ondaatje. A father and his two daughters Claire and Anna, not twins but inseparable as if they were, and a slightly older boy, Cooper, work a farm near Petaluma, California in the late 1960s. Ondaatje uses imagery, the power of two-ness or twins in the telling of this story, almost two separate books. The characters cross paths but do not return to any semblance of togetherness in the real sense, but each has imprinted the other two. The Leavers, by Lisa Ko. Another book about immigrants, a Chinese-born mother leaves rural village to go to NYC, pregnant, penniless, trying to make new life. She eventually is deported back to China, leaving her son and partner in the dark as to why she left and where she is. Son is adopted by white, professional couple, but his bond to his mother is thick. The story threads between mother and son, where is home and who is family, issues of transnational adoption, “fitting in,” finding oneself through others. Disappearing Earth, by Julia Philips. Two young “white” Russian girls are kidnapped from a small town in Kamchatska, near the Pacific Ocean. The author writes the story in chapters, with a different character the focus of each chapter, delineating the difference in treatment of ‘native’ Russians (Indigenous) and white Russians. Each character has some connection to the missing girls, whether the police detective, a woman whose own daughter, although much older, also went missing, the girls’ mother, etc., with the theme weaving throughout the book. The despair of the cold, near artic climate is also a character as the dark winter nights or endless summer days impact the individual characters.

Trilogy and Quartet

The Outline Trilogy, by Rachel Cusk: Outline, part one. The protagonist is a British writer who travels to Athens to teach a writing course. Through ten chapters, the nameless narrator encounters several individuals, which foster conversations, allegedly about the acquaintances, but ultimately we learn the “outline” of the narrator as she struggles with a new divorce, navigating her children still at home, wondering about her role, her place, who she now is. Transit, part two. Cusk continues with her British writer making her way (her “transit”) from stable marriage to purchasing a run-down house (and beginning remodeling) in a “good neighborhood” in London with her two sons. Similar to “Outline,” the protagonist by listening and questioning her friends to find answers, perhaps, to her own wonderings and questioning finds her footing with this new life. Kudos, the third book of the trilogy, continues the narrative of Faye. In each of her encounters with fellow travelers, conference attendees, acquaintances, she asks searing, deep questions about life, love, fate, religion, social justice, family. The conversations are framed to elicit varying points of view, partly to understand Faye’s positions through her questioning, but also to get to the universal crux of what is important in our lives.

Autumn, by Ali Smith, the first in the series of four books ostensibly about seasons. The starting place is 2015 post-Brexit referendum in Britain with all its uncertainty along with pressing immigrant concerns. The ultimate theme is about time, it’s not linear; it’s not distinct; it can be changed by memories, by dreams, by friendships. Elisabeth reads the opening lines of “A Tale of Two Cities” [“It was the best of times. It was the worst of times.”], which sear my brain as we experience this time of pandemic, stay-at-home, changing of social values, physical distancing, surreal daily updates of statistics (are they real?), illness, death.

Miscellaneous

*Where the Crawdads Sing, by Delia Owens. Again, a favorite. This first novel celebrates the low country of North Carolina, the marsh and swamps between the land and the ocean, the birds, the centuries old traditions, the class distinctions. The novel is one of place but also a coming-of-age story, with elements of loneliness, family, trust, abuse and neglect, opening oneself up without getting hurt. *Transcendent Kingdom, by Yaa Gyasi. A book about a family of immigrants from Ghana, the daughter, Gifty, loses her brother, Nana, to opioid addiction, her father returns to his native Ghana, and her mother becomes lost to depression. Raised in a religious home and ‘saved by Jesus’, she questions her religious faith as her brilliance in science shines, where she tries to understand restraint v. reward (ultimately seeking understanding of addiction). Family provides the backdrop as well as culture for this testament to sibling bonds and longings for mother, striving to be a good daughter, maneuvering childhood (and grief) without role models. The Lying Life of Adults, by Elena Ferrante. In classic Ferrante style, this novel delves into the lives of the women of Naples, here, thirteen-year-old Giovanna, her family, friends, and neighborhood. The distinction is again drawn between “upper” sophisticated Naples and the “lower” part of the city, industrial, poor, with dialect-focused language. Giovanna navigates her inner world, struggling to find herself after portrayed as “ugly” like her father’s estranged, manipulative sister. Ferrante brings us into the world of the adolescent, on the brink of adulthood, testing her family, becoming the go-between for her aunt, trying to understand the lies—and truths—of her childhood. What is essential for relationships, how does one learn from people once close then distant, who does one believe?

The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea, by Yukio Mishima. Written in mid-1960s, a group of teen-age boys in Japan has created an ideology where fathers are evil, among other complaints. The “chief” encourages the group in nihilism and unconscionable acts, reasoning that until they’re fourteen years old, they cannot be accused or convicted of crimes like murder. The group decides a sailor, step-father to one of the boys, must meet the ultimate fate, death, for trying to be a father to Norobu and his other “bad acts”. Without much thought, the boys violently kill the sailor. Their innocence is a falsehood; their acts cruel and murderous; their remorse, non-existent. The Pickup, by Nadine Gordimer. Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, this book centers on white, South African woman who believes she falls in love with a black man. The primary characters hide behind themselves, not revealing their real selves to one another. The drama of conflicting cultures, immigration, privileged world status v. the invisible, the story turns what we know or think we know of those to whom we are close on its head. Gordimer emphasizes “place,” whether a foreign country, one’s home country, the desert, a café, each with its pull and boundaries. Magpie Murders (Susan Reyland #1), by Anthony Horowitz. A twist on the classic British “whodunnit,” with a story within a story. Puzzles, anagrams, word play, two supposed murders, a small village, standard suspects, halfway through the book, an unseen twist and another murder; the author’s editor becomes a detective.

Goddesses, Witches, and Odysseus

*Circe, by Madeline Miller. This story has Titans, Olympians, Monsters, and Mortals who come together in this novel about Circle, daughter of Helios, the sun. Exiled to an island by her father, Circle, a nymph who learns and practices witchcraft, is despised by her siblings, threatened by gods, ravaged by drunken sailors, loved, briefly, by the mortals Daedalus and Odysseus. Her life is counted in the thousands of years, her despair and exile infinite, yet she finds beauty in the animals and plants of her island, gives safe passage to others, and is ultimately torn between her immortal life as a god and the lives of her mortal lovers. A fascinating narrative of historical and storied events, bringing together much of the mythological and ancient world, this tale is one of a strong woman who defied expectations, experienced hate and cruelty and love, made choices, some good, some bad, as she finds peace.)

Next Year

The “to-be-read” shelf of books and all those scrapes of paper listing book recommendations constantly remind me of what a rich world reading is. I’ll never be able to read all the books I want to read while finding more myself comfortable not finishing a book that doesn’t meet my expectations. I delight in learning of others’ favorite books and exploring the magical world of words that many are able to create. As always, I eagerly embrace another year of reading—and any suggestions!