The fog was beginning to shroud the mountains to the west. Mars rising, its beacon bright as a full moon lit the backdrop. Christopher and I walked above the Eel River. It meanders through meadows and dairy farms at this point in its journey to the ocean. The evening winds rustled the several lone pine trees and dry, late summer grasses that lined the pathway. The steady hum of cars and trucks on the nearby highway accompanied the crickets, night birds and lowing cows in the neighboring farms.

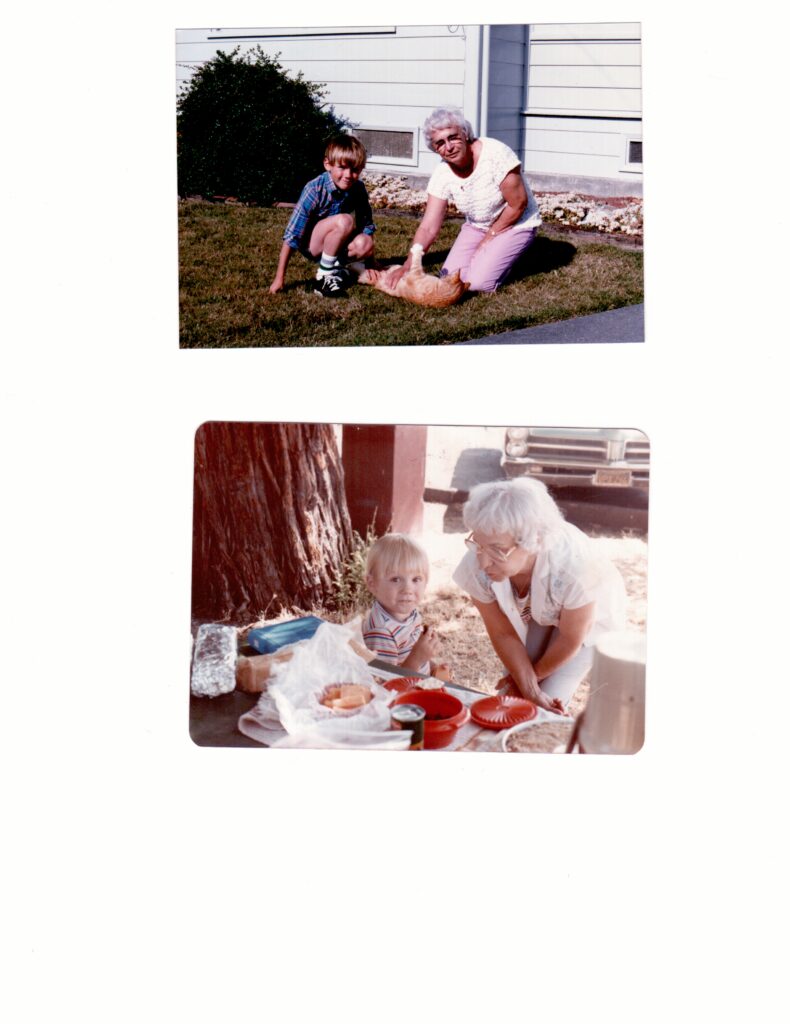

Alice and Christopher, birthday picnic near Clear Lake, California (typically custody exchange place)

We were quiet, enjoying the stroll, each of us immersed in our own thoughts. Our silhouettes are similar, long and lean. Our shadows danced together and then pulled apart in the dusky light. Christopher bent slightly forward, hands in his pockets, hair shaggy in the breeze, feet crunching the gravelly soil of the trail. We both relished stretching our legs after the long drive. How many miles have we walked together? How many times has he been at my side? He clutched my leg as a toddler, held my hand as a shy kindergartner, proudly stood near me after various graduations, and encouraged me to scramble high mountain peaks. That night we truly shared a bond as we contemplated the upcoming funeral service for our dear, beloved Alice.

We will honor her. We will mourn her. We will feel an enormous void. We will miss her wisdom, love, and homemade cookies. She was so integral, and necessary, to our lives. Even today, nearly two weeks after her death, I caught myself short, sadly remembering to change one of my rituals. Christopher had called with news of his first week teaching at Skidmore College in upstate New York. His students are thoughtful and engaged. He hiked and picnicked with two friends in the Adirondacks. He is settling into his “north country” house, complete with enclosed winter porch, bedrooms under the eaves, wood burning stove. I sat at my computer, ready to send a quick email to Alice, conveying the news. She savored receiving messages with my name as the sender and her “other grandchild” as the subject. She shared in all our “firsts”. Of course, I realized that she was no longer at the other end of the ether world. I will miss our missives.

I did not know if Christopher would be ready to express his feelings about Alice. Barely twelve months ago, his best “first friend” died in a horrible automobile accident in Ghana. He has not yet digested, fully, the fact of Leah’s death. She was young and vital, just beginning to find her place in the world. Christopher has mourned Leah simultaneously with anchoring their mutual friends’ grief. Alice was 90 years old, aware of and prepared for her death, still spry and curious. She was able to say her good-byes to those who were important to her. Leah did not have that opportunity, instead dying at a rural clinic thousands of miles from friends and family.

Both these women were so significant to my son. Alice was his buoy, his safe harbor and guardian angel. Leah was his muse, gently prodding and challenging him to look at life in unique ways. How would he deal with this new loss?

With these thoughts swirling around, I gingerly changed the subject of our musings. Our pace quickened as the chill of the evening enveloped us.

“What is your best memory of Alice,” I shyly inquired.

We had just turned back toward the motel, the ambient lights of the small town to our left. A few stars had popped out above our heads to glitter the sky, welcoming Mars as their companion. There was a long pause, several minutes at least, as we continued our walk in the near dark. I sensed his shaping of words and thoughts before they were spoken.

“Well, I don’t have one specific thought at the moment. She always made me a sandwich before I left her house.”

“It’s funny the details that stay with us, don’t you think? She always packed a lunch, whether we were going for a short drive or to catch an airplane back to the east coast. Almost assuredly it contained a sandwich, freshly baked cookies, apple juice in a tiny can, an orange and carrot slices. She always had the right size zip lock bag for each piece of food.”

We quietly chuckled. Alice was everyone’s ideal of a grandmother. Her refrigerator was full of delectable goodies. Her kitchen counter was hidden beneath brightly colored tins of cookies, breads and candies. The fruit bowl overflowed with apples, grapes and bananas. She made certain that no one left her house hungry.

For the past week, from the moment I’d received Dale’s voice message, “I have bad news. Alice did not make it. She passed away this afternoon about 4:00. I’m sorry. Call if you want to speak more,” images and reminiscences of Alice had tumbled through my mind.

I don’t recall exactly when we became friends. She was the part-time book-keeper (her official title, although her contribution was so much more than that) at my then-husband’s law firm, in a small town in northern California. I suppose we met shortly after we arrived in Fortuna. My then husband, David, and I had traveled throughout northern California on our job and home search, looking for the perfect combination of beauty and hiking. We necessarily sought towns large enough to accommodate two lawyers, one experienced, one waiting for the bar examination results, but small enough for a sense of community.

Our job search ended here, three hundred miles north of San Francisco. This place felt like it could be home for a very long time. It had been for Alice and her family, generations of dairy farmers in Ferndale. Unfortunately, it was not to have a fairy tale ending for me.

During the six years I lived in Humboldt County, I learned the rudiments of becoming a lawyer, I developed enduring friendships with other “ex pats” from the city, I embraced running as a daily ritual and necessity, I became pregnant, I delivered my first son, I became divorced. I slowly became acquainted with Alice.

Avenue of the Giants, Humboldt County, California

She was lively, quick to smile, a blizzard of efficiency, truly a bright light in the often-foggy days. Sandwiched between my parents in age, like my father in temperament, she could have been my mother—but there the difference ended. The more natural pairing would have been with her son and his wife, certainly if one considered chronological age an important consideration in friendships. But she is the one who stepped into my life at its darkest moment and, in her inimitable manner, brought me into her orb without judgment, only pure love and compassion.

We were a study in contrasts: she, tiny, delicate, glistening white hair framing her round, open face, smooth Italian skin, smiling, always; me, long-limbed, brown-haired, freckles among the tanned face, more somber persona. She favored shoes, a closet full; I tended toward jeans and socks (when I wasn’t wearing my professional mantle of suit and high-heels). When we hugged (which we did a lot), I would bend my knees, stoop down and double my arms around her body, my Gulliver engulfing her Lilliputian.

Christopher’s reminiscences interrupted mine: “Do you remember how I spent the summer Mondays at her house? How old was I, six or seven? Garrett, Grant and I were always trying some new experiment, making mud pies out of her struggling flower beds, playing hide and seek in her barn, sitting on the tractor, pretending we were farmers like her husband, baking cookies without the help of recipes. Alice always maintained her, what should I say, her equanimity, never correcting us, never raising her voice, never saying we couldn’t try something, unless it was jumping from the barn loft to the hay bales below. She took the three of us in stride.”

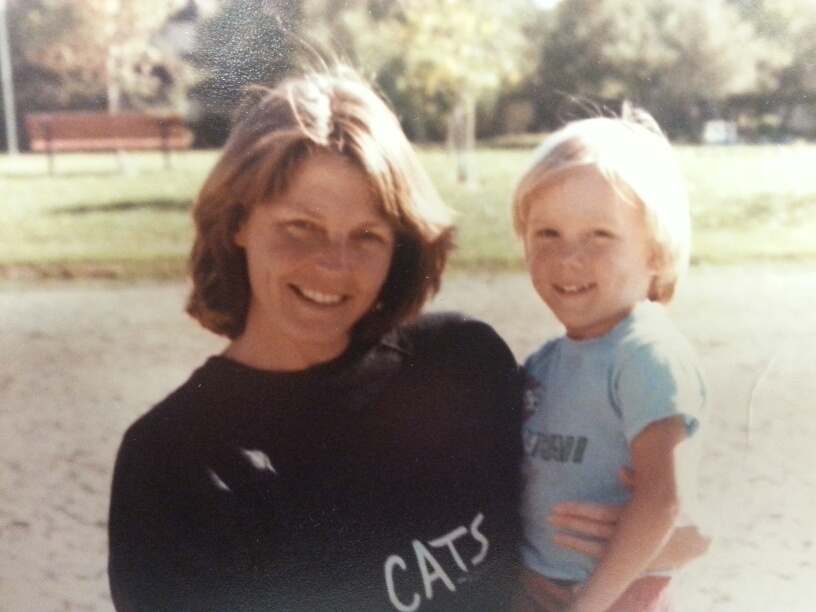

Christopher (age 3) and I, soon after we moved to Sacramento–on our own!

The three boys were a dervish of legs and arms, running to and fro, safe in the sheltered yard of Alice’s hundred-year-old house. Oh, I will miss her home, surrounded by acres of dairy land, a respite. We would stand in the glassed-in porch, capturing the afternoon warmth while the sun typically sank in the fog bank, rarely leaving a sunset. The warm oak floors, the multitude of rocking chairs, the smell of baking mixed with crackling wood greeted us each time we visited. At the end of the lane, the home was a small island of charm, a place where innocence really could have prevailed.

The memories are deep. Christopher slept in one of her cribs there as a baby, stumbled as a one year old taking his first steps, played with Alice’s grandsons during summer vacations, drove himself here as a teenager (with a sandwich freshly made and waiting for him). Even after he left California for college and graduate school, and then a post-doctoral program, Christopher stayed in contact with Alice. She would express amazement that he stopped by, wrote long and newsy, although infrequent, letters, and occasionally called from one of his innumerable road trips.

How could I forget my son’s summer days spent at Alice’s house? The custody arrangement with David was constant and hard (for me, at least): my toddler son spent three weeks in Sacramento with me, one week in Humboldt County with his father. The “exchange” often took place at a park in Lucerne, along Clear Lake. I loathed those Saturdays when I left Christopher with his father for another week’s visitation. Christopher and I waved as he rode away in his father’s car, not stopping until he was a speck in the distance. My two-and-a-half-hour drive back to Sacramento was inevitably lonely and desolate. I tried to fill the hole in my heart with Mussorgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition,” the powerful music swelling in the small car, distracting me from yet another parting from my son. My comfort: he would spend some of his time, always, in northern California not at his father’s house, but at Alice’s.

One scene: the second exchange of that first summer occurred around the time of Christopher’s second birthday. Alice drove with David and Christopher (this was the back-end of my son’s week with his father) to the soon-to-become too familiar half-way mark. She brought a party, Tupperware filled with fried chicken, crackers and cheese, carrot and celery slices, cookies, a cupcake with a candle. Her presence provided a buffer to an otherwise tense situation. I did not want my son to feel the distance and awkwardness between his parents, at least at his young age.

“She was neutral, balanced, I guess. She would ask me how you were, how my father was, how I was. She always got the answers eventually, gently prodding me, without me even realizing she was doing it.”

Christopher had not yet been born when his father first left me; only a few months old when the separation became permanent. I tried to shield him from knowledge of the circumstances as much as I was able. I tried not to belittle his father, to cooperate with the extensive visits up north, to keep an open mind that no matter my relationship with David, he was my son’s father. Alice was instrumental in smoothing the edges, although it must have been difficult for her. She cared for each of us.

She watched over Christopher, providing him constancy in an otherwise bifurcated childhood. She was my “Humboldt County eyes” when I was not there, calling me after his days, sharing their stories. A very shy child, he found a place to be a little boy without worry whether he was favoring one parent over the other. His smile and affection were huge for this woman. For this, my gratitude will always be insufficient. My long-ago “thank you’s” pale in comparison to what she gave to both of us.

I likely had placed Alice in an awkward position. David was a partner at the law firm; I was the only associate. Alice’s husband had died a few years before from a long, ugly bout with cancer. I think she found solace in her work, a break in her grieving. Then, I arrived with the baggage of being six and a half months pregnant, hearing from my husband that he loved another, while still loving me, the hole deeper than my soul.

That first night after fighting the news of David’s betrayal, sick with worry about my unborn child, I called Alice. I told her we could not come over to a previously planned dinner because “I didn’t feel well.” I lied. I could not yet share this burden with her. Within two days, I fled the land that had felt so right only a few years before, to my childhood home in southeastern Washington. I sought solace with my parents. Soon enough, I returned, though. I bravely decided I had as much right to be in Humboldt County as my husband. My friends were there, my job was there (although that, too, would become a casualty), and I was no longer a child that could be comforted by over-worried parents.

Alice welcomed me without question upon my return. I had stopped by her house, letting her see that I was physically well, that my unborn child was still kicking mercilessly. My words on the telephone had not been convincing and she was worried.

I despaired of hearing “You are so strong. We are amazed.” I wasn’t. Alice heard the soft crying at night, saw the fear in my eyes of becoming a first-time mother, perhaps a single mother. She willingly shared her home, her strength, her wisdom, during this time. She knew, more than I, that I could survive this trough.

She listened as much as I needed. She prepared her signature butter soup, lots of vegetables and “whatever is in the refrigerator” thrown in. During the next two months as my appetite plummeted, she would show up at my door step, picnic in tow, always with something enticing to eat. She would arrive at my house at dusk, taking time away from her own life, to sit with me, sometimes to chat, sometimes to share the quiet, just being with me. This would be a constant in our long-term friendship, the ability to talk a mile a minute or sit together to read, to think, without the necessity for any conversation between us. Oh, I will so miss those times.

Maybe I offered something to her, too? During these evenings, she slowly opened up about her life with Kenny, the courtship, the rushed wedding in San Francisco after news of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the twelve-hour train rides to visit him in the city while he was on active duty, the not-knowing for more than two years when he was in Europe during the war how or whether he would come home, the raising of two sons, the caring for her mother-in-law, Kenny’s battle with cancer, her career, her family, her dreams shattered, too.

I then asked the impossible of Alice. After I returned from Washington, I had started Lamaze classes. Natural child-birth was the rage in those days. I went to the first session alone as David was out of town. We attended the second one together. After the obligatory breathing exercises, we sat in the darkness as the teacher showed a movie about the birthing process. The underlying message was so clear; the soon-to-be mother should expect unequivocal support and trust from her partner. The tears flowed down my cheeks. I could not go through this with David. He had shattered my faith in him. I could not share this intense, intimate time with the man whose allegiance was so clearly divided. In hindsight, I believed I could put aside the reality of our situation. I was wrong. The betrayal was too fresh and close.

The next morning, Alice and I arrived early at the office, as we often did. Without thinking how I might disrupt her life, I approached her, tears welling once again in my eyes.

“Alice, can we talk?”

Her voice betrayed a hint of concern as she caught my puffy eyes.

“Of course. Let’s go to the break room. We can talk there. No one else is here yet. How are you doing?”

I almost cracked, the words creeping up from some place deep within my throat.

“Will you be my Lamaze partner? I cannot do it with David. It is too hard.”

Immediately, without pause, she answered, “When do we start?”

We did participate in the remaining Lamaze classes but the lessons did no help during labor; I could not focus on any semblance of rhythmic breathing. My memories are jumbled of that night, so fraught with anxiety: my mother arriving that morning only to express her inimitable critical opinions about my errant husband (I had to agree with her, but the timing was not right); the difficult labor, the baby’s heart in distress; Alice at my side, her soothing voice lulling me away from the pain and worry; the night becoming early morning. And then, I gave birth to Christopher, only to have him whisked away by the nurses. Alice held him first once the nurses confirmed he was healthy—and beautiful. She beamed as if he were her own son. We cried together in joy and wonder.

How could I ever repay that debt? Did she realize the critical role she played in my life? Did I tell her enough how much I loved her, not as a mother (which connotes, to me, an imbalance in the relationship), but as a true friend? Did I listen enough to her?

Early one morning, about five weeks before Alice died, I received an ominous email: “Dear Patricia. I have not good news. Tom and Mary went home and he came right back alone because I am headed in about a half hour to hospital for some rather serious surgery. Tom will try to call or email you later today. We are not sure of the outcome. I have decided I cannot live alone so we are working on that, too.”

My heart skipped as the words slowly unfolded. What was this “serious surgery”? Why the decision, now, to move to a care home? For years, she’d expressed concern about spending another winter alone in her house. She dreaded the long, wet, dark days of north coast weather. Often her lane would be flooded and she’d be trapped, not able to drive. The dark evenings alone were wearing. She was starting to fall more often. The artificial hips, such a boon when they were first installed, were failing. Her final written words, “I hope I can talk soon,” portended a change, a reflection I’d not sensed before in our conversations.

I waited, anxiously, for the telephone call from Tom, her older son. Finally, two days after the email, we spoke. She survived the surgery well. Her physician predicted only a few more days in the hospital before she could return home. One of her favorite nieces was there, coordinating medicines, follow-up appointments, keeping the house in order. Relieved, I vowed to call her that morning.

Then, complications, blood transfusions, unknown infections turned the few days in the hospital into eleven. Alice and I spoke several times while she was there. We also chatted on her first day home. Her tone was different, weary and introspective.

“I almost didn’t make it. Too much blood loss. My legs were so swollen, then all the drugs. I am so tired. I just don’t know.”

We didn’t talk about her moving to an assisted living facility. She had tabled the idea to get settled in the care home sooner than later. She did not want to be a burden on her children. The hospital stint, I think, scared her more than she may have let on.

Yet again, in these last days, Alice’s primary concern was of others, not herself. Her house was her refuge, too. She’d lived there for over sixty years. Even when she was immobile from various surgeries or illnesses, she would light her fire, wrap herself in blankets and read. She could look out any window in any direction and see the farm land where Kenny had raised dairy cattle. She could see the lights of her younger son’s home across the way, keeping watch on her. How would she survive living in town, one bedroom as her home, sharing meals with strangers? She would make it work regardless of the dislocation and heartache of moving. I worried, though.

The bane of elderly patients, pneumonia, interrupted all plans of moving. It is stealthy and crafty. It hit unexpectedly, seemed to move on quickly, then overnight, it caught hold of Alice, acute respiratory distress. She denied any aggressive intervention. She made it clear she was ready to go. She woke on the last day of her life perplexed that she was still in the hospital! And then, softly and quietly, she slipped away, in her fashion, without fanfare, her sons at her side.

Thoughtful and sharp until the last few hours when her body finally broke down, she died as graciously as she had lived. She will always and forever be a beacon of how to live one’s life and how to say good-bye.

After the funeral service, I spoke briefly to Alice’s daughter-in-law, Mary. A school-teacher, she had presented the first eulogy. Mary described a family trip to Washington, D.C. when Alice’s grandchildren were 8, 10 and 15. As the kids ran around, tired of museums, Alice noticed the Petersen House, the boarding house where Abraham Lincoln was taken after being fatally shot by Booth. She insisted that a family photo be taken in front of the house sign, excited that the spelling of “Petersen” was the same as her name.

Mary reminisced that Alice’s home was, in its own way, a boarding house. Young and old, family and friends, even friends of friends, were welcome there. Christopher and I, sitting together in the church pew, glanced at each other and smiled. Just this last holiday season his friend, Iris, had stopped by Alice’s house. She was on her way from Portland to San Francisco. Alice embraced her, chatted around the fire and woke early to make pancakes and a lunch. She admonished Iris to call once she arrived at her destination. Otherwise, Alice would worry.

As I was about to turn away from Mary, wanting others to have the opportunity to share their condolences, she said to me, “You were the daughter she never had.”

Those words, so unrehearsed, so precious, filled my heart. Perhaps I had repaid part of my decades-old debt to Alice. Only she will know.

Beautiful story. I enjoy your writing.

Warmly,

Peggy Winters Anger