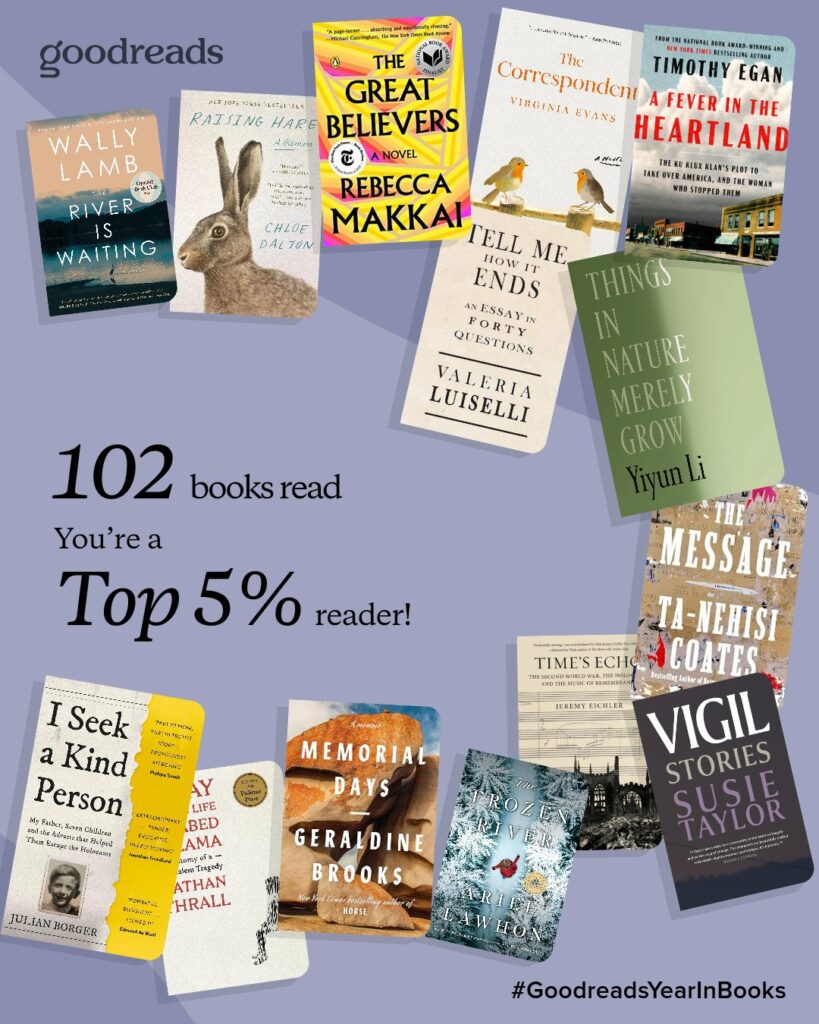

This year was full of tumult and change, yet grounding me in all things is reading. And what a year for incredible books to read, to study, to contemplate, to wonder! Favorite authors (Ian McEwan, Colum McCann, Sue Monk Kidd, Barbara Kingsolver, Ocean Vuong, Han Kang), heart-breaking stories (“All The Colors of the Dark,” “Grace,” so many others), history and biography (“The Romantic Odyssey of Fancy and Robert Louis Stevenson”), memoir/essays, nature (“Raising Hare”), Pulitzer Prize winners, Booker Prize winners, new-to-me authors (Keran Desai, Amity Gaige), Chinese short stories, non-American authors–the mixture was as varied as each voice telling its story. I am dismayed reading the statistics on the decline in book reading in America: how can that be when the breadth and depth of what is written is so rich?

Ian McEwan writes in “All We Can Know,” about biographers a hundred years from now, giving their lives to research a lost poem. Why, he asks? “It’s about what biographers owe their subjects. It’s about the nature of history. It’s about letters, journals, emails and the other things we leave behind.“

Isn’t that why we read? To learn, to discover, to imagine, to be swept away? It’s the past, present and future. It’s what we leave behind and what we hope to find again.

NON-FICTION:

BIOGRAPHY:

A Day in the Life of Abed Salama: Anatomy of a Jerusalem Tragedy, by Nathan Thrall (On a rainy, windy morning in February 2012, on a highway outside of Jerusalem, an 18-wheeler collided with a school bus filled with kindergartners and their teachers. The bus rolled over and landed on its side, door-side down, and burst into flames. One teacher and six children died. Some of the survivors were so badly burned that a local man who broke a window and climbed into the bus to pull the children out couldn’t recognize them as human. The passengers were Palestinian, as was the truck driver. Unlike them, however, he held a coveted blue ID, a kind of passport that allows for greater freedom of movement in and around Jerusalem. The book follows a Palestinian man named Abed Salama whose 5-year-old son, Milad, was on the bus. By the time Abed reaches the site of the accident, the children have already been rushed to hospitals by helpful good Samaritans and United Nations health workers who chanced upon the crash. Abed must decide how to search for his son, but given his particular identity card, his options are limited. The author weaves scenes from the aftermath of the accident with passages of historical context that explain the physical and legal boundaries that shape the lives of Palestinians living in East Jerusalem. Tragic, complex, human.)

Every Valley, The Desperate Lives and Troubled Times that Made Handel’s Messiah, Charles King (A studied biography embedded in the history of Britain and Europe in the 1500’s-1700s, where wars, poverty, religions, The Restoration, battles among kings and pretenders, the idea of hope, set the background for Britain’s emergence as a place of music. George Frederick Handel, German (Saxon) by birth, steeped in Italian music, naturalized British citizen, was musician to princes and kings, famous in his life-time. The title “every valley” is reference to verse in Isiah about hope, raising up valleys and flattening mountains and rivers. The Messiah is the most-listened (and performed) piece of music in history, originally perhaps a religious ode based on Christ’s birth, death, and ascension but now more secular, performed at the Christmas holidays and not Easter. The story of the men and women behind the music and their relationships to Handel; unfortunately some were very ancillary and the biographical parts related directly to Handel not as fleshed out as they could have been.)

A Wilder Shore, the Romantic Odyssey of Fanny and Robert Lewis Stephenson, Camille Peri (Kirkus Review: Journalist Peri draws on considerable archival sources to create a perceptive portrait of the unlikely marriage of Robert Louis Stevenson (1850-1894) and Fanny Osbourne (1840-1914). Stevenson, “a university-educated writer from a prominent family in Scotland,” had just passed the Scottish bar. Fanny grew up in Indiana, lived in a mining camp with her philandering husband and three children, and most recently had settled in San Francisco. Eager to escape a stultifying marriage, grieving the death of her eldest son, she took her remaining children to France, where she and her daughter planned to study art. There she met Stevenson, also eager to escape; he was intent on pursuing a writing career, much to his father’s disappointment. They were a study in contrasts: Stevenson, skinny, unkempt, sickly; Fanny, attractive and forthright, with a personality “as big as the American frontier, with a blend of female sensuality and masculine swagger.” They quickly fell in love. Peri recounts the couple’s peripatetic journeys. They visited with Stevenson’s family in Edinburgh and traveled to Davos, Switzerland, for tuberculosis treatment. In the English resort town Bournemouth, they kindled a friendship with Henry James, in town to care for his sister. They went to the U.S., where the author of Treasure Island, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and Kidnapped was hailed as a celebrity, and to French Polynesia on the first leg of two years of travels. A chain smoker with many medical maladies, Stevenson died in Samoa. Fanny proved more than a caregiver for her invalid husband: “She was a sharp critic and observer, and had a colorful imagination, qualities that he valued and relied on,” Peri comments, noting that he left his writing at her bedside each night for her to critique. Although Osbourne’s work came after Stevenson’s health and writing, Peri’s extensive exegeses of her stories judge them to “sit comfortably and creditably among those of other female magazine writers of her day.” A richly detailed chronicle of two eventful lives.)

HISTORY:

Time’s Echo: The Second World War, the Holocaust, and the Music of Remembrance, Jeremy Eichler (Using the music and lives of four composers/musicians [Arnold Schoenberg, Richard Strauss, Dmitri Shostakovich, Benjamin Britten] who composed music during and after World War II, to try to understand more fully the war, the conflict of nations over power and territory, and the Holocaust, the branding of specific groups of people as less than human with the goal to exterminate them, and how the different nations thought of their legacy and the facts/truth of what occurred. “Music is time’s echo,” a way to more fully understand history and its consequences, the memory of the times, the embracing of it by deep listening to sound, a way to remember that is more powerful than words themselves, a way of keeping memory when books/words/monuments no longer suffice or disappear. “Works conceived as musical memorials do all of this actively. They request that we listen to the past through music’s ears, that we recall particular moments linked in a history of catastrophe, and that this memory then inform our choices of the values we wish to perpetuate into the future… To listen deeply to any older music in these ways is to perform an act of empathy angled toward the past. And like all acts of empathy, it takes us beyond the confines of the self, liberating us outward into the world.”)

Madame Fourcade’s Secret War: The Daring Young Woman Who Led France’s Largest Spy Network Against Hitler, Lynne Olson (In 1941, Marie-Madeleine Fourcade, a thirty-one-year-old Frenchwoman and mother of two, became leader of a vast Resistance intelligence organization in France—the only woman to emerge as a chef de résistance during the war. Strong-willed, independent, and a lifelong rebel against her country’s conservative, patriarchal society, Fourcade was temperamentally made for the job. Her group’s name was Alliance, but the Gestapo dubbed it Noah’s Ark because its agents used the names of animals as their aliases. No other French spy network lasted as long or supplied as much crucial intelligence, including providing American and British military commanders with a 55-foot-long map of the beaches and roads on which the Allies would land on D-Day, showing every German gun emplacement, fortification, and beach obstacle along the Normandy coast. The Gestapo pursued Fourcade and Alliance relentlessly, capturing, torturing, and executing hundreds of her three thousand agents. Fascinating insight into Fourcade as well as the British and Allied Forces’ reliance on French resistance groups.)

A Fever in the Heartland, The Ku Klux Plan to Take over America, and the Woman who Stopped Them, Timothy Egan (Egan gives us a riveting saga of how a predatory con man (D.C. Stephenson) became one of the most powerful people in 1920s America, Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan, with a plan to rule the country. NY Times: “The 1920s marked “the second coming of the K.K.K.” The new Klan drew on the same deep reservoir of racial animus, the same mythology of white victimhood, as its 19th-century antecedent. Its methods, too, had their roots in the Reconstruction era: torture, beatings, lynchings. But the second Klan sought, and to an astonishing degree achieved, an appeal beyond the Old Confederacy. It offered a more expansive set of resentments, providing more points of entry for aggrieved white Protestants. Racial purists were armed with the so-called science of eugenics and stoked with fears of being replaced by “insane, diseased” Catholics and Jews. Moral purists and traditionalists were called from the pulpit to wage war against modernity — enlisting in K.K.K. vice squads that beat adulterers and smashed up speakeasies. The Klan did more, in this period, than raise the fiery cross. For a startlingly large number of Americans, Egan writes, the Klan also “gave meaning, shape and purpose to the days.”” I learned so much from this historical account of the Klan, its adherents, it penetration in government at all levels.)

MEMOIR/ESSAYS:

Artful, Ali Smith (“Artful” contains a series of lectures, “On Time”, “On Form”, “On Edge” and “On Offer and On Reflection,” given at St. Anne’s College, Oxford. Imaginative (the writer grieving her recently-deceased lover who comes back to haunt her), riffing about art and literature (Dickens, Shakespeare, Kathryn Mansfield, Freud, Pasternak, EM Forster, so many writers), reflecting on the gods and God, giving and receiving, the relationship between thought and art. The Guardian: “But even that doesn’t begin to describe this all-singing, all-dancing exploration of how thought feeds off words and words nourish thought. It launches you on daydreams through thickets of words, it runs splashing through phrases as if they were puddles, or it drops clauses into the stream, Poohsticks style, and rushes to the other side of the bridge to watch them emerge.” Original, requires slow reading and thought, difficult to describe.)

The Lady’s Handbook of her Mysterious Illness, Sarah Ramey (The Lady’s Handbook for Her Mysterious Illness is a memoir with a mission: to help the millions of (mostly) women who suffer from unnamed or misunderstood conditions—autoimmune illnesses, fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome, chronic Lyme disease, chronic pain, and many more. Sarah describes in excruciating detail her illnesses, and along the way, encounters other women with long-term, chronic, undiagnosed illnesses that interrupt their lives, cause extreme pain, and, sometimes unexpectedly, encourage them to push themselves to achieve successes despite/because of the diseases. Disheartening and disappointing indictment of medical system. She discovers The Heroine’s Journey as the place out of which she might find salvation and life: “The feminine journey is one of continued, conscious cycling through darkness into rebirth—learning to see and gather wisdom in the dark, rather than trying to slay the dark.” Functional medicine is ultimately the route that helped her find a way out of the dark and gain back some health.)

Memorial Days, a Memoir, Geraldine Brooks (Brooks husband, Tony Horwitz, died of unexpected heart attack in 2019 at the age of sixty. Brooks didn’t properly grieve for him, caught up in all the post-death details and finishing her book, “Horse.” Three years later, she went to isolated island off Australian coast, alone, with time to think about their lives together, the what might have been, the deep love the two shared, the remembering, the homage to him—time to grieve in silence.)

The Unforgiving Hours: The Grit, Resilience, and Perseverance at the Heart of Endurance Sports, Shannon Hogan (Through the exploration of incredible physical feats—some well-known and some only passed around watering holes and campfires—endurance athlete and journalist Shannon Hogan takes us into the world of those who have pushed themselves through the “unforgiving hours” to achieve greatness and redefine modern outdoor adventuring.From the frozen wilds of Alaska’s treacherous trails to the unyielding currents of Puget Sound and Canada’s Inside Passage, from the rugged majesty of Colorado’s peaks to the vibrant depths of Costa Rica’s rainforests, Hogan offers us an intimate window into the toughest contests in sports. These stories of ordinary women and men who kept going even when things go wrong, especially when the weather and tides do not cooperate, attest to the drive, grit, and patience that exists in all of us. Their triumphs, large and small, are a testament to the power of adaptability, passion, and the sheer will to keep going, one breath, one step, one stroke, and one mile at a time.)

Tell Me How It Ends, An Essay in Forty Questions, Valeria Luiselli (The author is translator for undocumented children crossing the Mexican border into the US, using the forty questions asked to determine whether the child(ren) is to be deported back to home country or allowed to stay in US. The narrative centers around their answers, describing the conditions, the “why” they have come to US (“pulled” because parents or relatives may be here or “pushed” because of conditions in their home country). Heart-breaking, informative: how are these children able to go through this hell—other than a dream that perhaps life is better here, despite the anti-immigrant perspective of so many Americans?)

Notes to John, Joan Didion (Posthumous publication of parts of Didion’s journal with entries from December 1999-January 2002, mostly about her adopted daughter, Quintana Roo, who died at age of 39, mental health, alcoholism, etc. NYTIMES: “Notes to John is rough, incomplete, raises more questions than it answers, slightly sordid and absolutely fascinating.” Curious to me how heirs decided to publish this very personal account of family issues, Joan’s sessions with her psychiatrist and Quintana’s dependence on her parents, alcohol, feeling isolated, even as Joan discovers some of the same characteristics in her childhood and relationship with her parents. Felt invasive reading these notes but perhaps some understanding of Didion and John Dunne, her husband, and their relationship.)

Knife, Meditations after an Attempted Murder, Salman Rushdie (Memoir about the knife attack on Rushdie as he was about to give a lecture at Chautauqua Institute in NY about safety for writers: the horrific incident, his recovery, the love and help of his wife, Eliza, and family, doctors, PT, OT. Combined with some of Rushdie’s history, family dynamics, questions of freedom and safety, self-reflection about wanting to live, how to obtain privacy; his imaginary conversation with Mr. A., the attempted assassin, a young man, radicalized, but without clear direction or reasoning for the specific attack on Rushdie.)

The Invention of Solitude, Paul Auster (The Invention of Solitude, split into two stylistically separate sections, established Paul Auster’s reputation as a major voice in American literature. The first section, “Portrait of an Invisible Man,” explores Auster’s memories and feelings after the death of his father, a distant, undemonstrative, almost cold man. As he attends to his father’s business affairs and sifts through his effects, Auster uncovers a sixty-year-old family murder mystery that sheds light on his father’s elusive character. In “The Book of Memory,” the perspective shifts from Auster’s identity as a son to his role as a father. Through a mosaic of images, coincidences, and associations, the narrator, “A,” contemplates his separation from his son, his dying grandfather, and the solitary nature of storytelling and writing. Written in third person, in fragments, with references to other writers, being in a closed room, to capture memories—not as readable.)

I Seek a Kind Person: My Father, Seven Children, and the Adverts that Helped Them Escape the Holocaust, Julian Borger (This gripping family memoir of grief, courage, and hope tells the hidden stories of children who escaped the Holocaust, building connections across generations and continents. In 1938, Jewish families are scrambling to flee Vienna. Desperate, they take out advertisements offering their children into the safe keeping of readers of a British newspaper, the Manchester Guardian. 83 years later, Guardian journalist Julian Borger comes across the ad that saved his father, Robert, from the Nazis. From a Viennese radio shop to the Shanghai ghetto, internment camps and family homes across Britain, the deep forests and concentration camps of Nazi Germany, smugglers saving Jewish lives in Holland, an improbable French Resistance cell, and a redemptive story of survival in New York, Borger unearths the astonishing journeys of the children at the hands of fate, their stories of trauma and the kindness of strangers.)

Things in Nature Merely Grow, Yiyun Li (The loss of two sons to suicide—unimaginable and unfathomable, but Li writes in a way that helps us understand the abyss of being a parent no longer with children to parent. “There is no good way to say this,” Yiyun Li writes at the beginning of this book. “There is no good way to state these facts, which must be acknowledged. My husband and I had two children and lost them both: Vincent in 2017, at sixteen, James in 2024, at nineteen. Both chose suicide, and both died not far from home.” Words fall short. It takes only an instant for death to become fact, “a single point in a timeline.” Living now on this single point, Li turns to thinking and reasoning and searching for words that might hold a place for James. Li does what she can: “doing the things that work,” including not just writing but gardening, reading Camus and Wittgenstein, learning the piano, and living thinkingly alongside death. This is a book for James, but it is not a book about grieving or mourning. As Li writes, “The verb that does not die is to be. Vincent was and is and will always be Vincent. James was and is and will always be James. We were and are and will always be their parents. There is no now and then, now and later, only, now and now and now and now.”)

The Return: Fathers, Sons and the Land in Between, Hisham Matar (Pulitzer Prize Winner. In 2012, after the overthrow of Libyan ruler, Qaddafi, the acclaimed novelist Hisham Matar journeys to his native Libya after an absence of thirty years. When he was twelve, Matar and his family went into political exile. Eight years later Matar’s father, a former diplomat and military man turned brave political dissident, was kidnapped from the streets of Cairo by the Libyan government and is believed to have been held in the regime’s most notorious prison. Now, the prisons are empty and little hope remains that Jaballa Matar will be found alive. Yet, as the author writes, hope is “persistent and cunning.” The Return is a brilliant portrait of a country and a people on the cusp of immense change, a disturbing and timeless depiction of the monstrous nature of absolute power, and a narrative of what “home” sounds, smells, tastes, looks, and feels like in one’s memories and upon return after decades away.)

Shattering the Mirror, One Woman’s Journey of Healing, Lena Fein ([Lisa Frankel Wade] Lena’s personal journey from a verbally abusive, non-loving childhood, to a successful career in high tech, two marriages, two children, the underlying feeling of shame, that she wasn’t enough, that she wasn’t loved, filled with rage, finally taking control of her story through therapy, self-expression, and the shedding of the negative influences. The harshness of a mother’s love to a brief moment of kindness and tenderness when she died strongly impacted Lena to change the trajectory of her life. Brave and courageous to tell the story, the writing is spare, the themes too familiar to many of us.)

Moonglow, a Novel, Michael Chabon (“The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay,” eight+ novels. A fictional non-fiction narrative of the last week of Chabon’s grandfather’s life, where the old man finally tells the story, sometimes true, other times not, of his life. Chabon explores the boundaries between fact and fiction, the “true story” beneath the stories. The Guardian: “The grandfather, an unnamed engineer, has lived a vivid and rambunctious life and now, dying of bone cancer and loose tongued from painkillers, he relates his history to Mike with the garrulousness of one who knows his time is short. The novel is structured haphazardly as far as chronology goes, leaping from the grandfather’s wartime exploits to his marriage to a period in jail. These jumps in time could be discombobulating, but we recognise a deeper logic at work in their construction – memory, hunting in the dark for truths and affinities within the seeming randomness of a life.” A long read, at times sluggish, other times brilliant.)

The Enigma of Arrival, V.S. Naipaul (The story of a writer’s singular journey – from one place to another, and from one state of mind to another. At the midpoint of the century, the narrator leaves the British colony of Trinidad and comes to the ancient countryside of England. And from within the story of this journey – of departure and arrival, alienation and familiarity, home and homelessness – the writer reveals how, cut off from his “first” life in Trinidad, he enters a “second childhood of seeing and learning. He observes the gradual but profound and permanent changes wrought on the English landscape by the march of “progress”, as an old world is lost to the relentless drift of people and things over the face of the earth. But while this is a novel of dignity, compassion and candor it is also, perhaps surprisingly, a work of celebration.”)

The Message, Ta Nehisi Coates (Part memoir, travelogue, primer on writing. The Oberlin Review:

“[Coates’s] reflections remind us that writing is more than a craft; it is a duty, a means of preserving truth, and a path to liberation. Through his travels and reflections, Coates shows that we each have the power to honor our past and to fight for a just future — whether by sharing stories of resilience from Senegal, standing up to censorship in South Carolina, or bearing witness to struggles in the West Bank.”—analogies to white supremacy and experience of Blacks in America.)

The Answer is in the Wound, Kelly Sundberg (A memoir of trauma and survival as the author, in essay form, writes of her childhood and young adulthood, growing up in rural Idaho to conservative Christian parents and living in an abusive marriage. Striving to overcome her divorce, the grief and pain of married life, raising her son as a single mother, and the effects of “normalization” of violence against women, Sundberg describes in heart-wrenching and heart-warming form the nonlinear arc to recovery, spirituality, and post-PTSD life.)

Writing, Creativity and Soul, Sue Monk Kidd (“I’ve tried to tell the story of my writing life and to offer the most significant things I’ve learned about the mystery and method of writing and the presence of soul in the creative process.” One can feel Sue Monk Kidd’s deep, abiding passion for writing, the essence of her creative energy, the soul that she shares through stories. A primer about writing, it is much more—the process by which she writes, the anecdotes about some of her books, the fears, frustrations, and joy of a completed sentence. Brilliant!)

SCIENCE/NATURE:

Every Living Thing, The Great and Deadly Race to Know All Life, Jason Roberts (Eighteenth century, Carl Linnaeus and Georges-Louis de Buffon dedicated their lives to identifying and describing all life on Earth. Polar opposites, Buffon studied evolution and genetics, warned of global climate change, and argued against prejudice. Linnaeus gave concepts of mammal, primate and Homo Sapiens, but denied that species change and promulgated racist pseudoscience. They thought they could catalog all of life’s species, falling far short of their goals. In the process, they articulated starkly divergent views on nature, on humanity’s role in shaping the fate of our planet, and on humanity itself. The final chapters bring forward their work from Darwin, Mendel and Huxley to the present, with DNA, genetics, evolution, ecology, the Anthropocene era. Truly a fascinating work!)

Raising Hare, a Memoir, Chloe Dalton (In February 2021, Dalton stumbles upon a newborn hare—a leveret—that had been chased by a dog. Fearing for its life, she brings it home, only to discover how difficult it is to rear a wild hare, most of whom perish in captivity from either shock or starvation. Through trial and error, she learns to feed and care for the leveret with every intention of returning it to the wilderness. Instead, it becomes her constant companion, wandering the fields and woods at night and returning to Dalton’s house by day. Though Dalton feared that the hare would be preyed upon by foxes, weasels, feral cats, raptors, or even people, she never tried to restrict it to the house. Each time the hare leaves, Chloe knows she may never see it again. Yet she also understands that to confine it would be its own kind of death. Raising Hare chronicles their journey together while also taking a deep dive into the lives and nature of hares, and the way they have been viewed historically in art, literature, and folklore. We witness firsthand the joy at this extraordinary relationship between human and animal, which serves as a reminder that the best things, and most beautiful experiences, arise when we least expect them. Dalton’s life changes as she slows down to relish each moment with the hare, and the countryside, letting loose of her highly charged, frenetic life as a political advisor.)

Encounters with the Archdruid, John McPhee (The narratives in this book are of journeys made in three wildernesses – on a coastal island, in a Washington state mountain range, and on the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon. The four men (focusing on Brower, head of the Sierra Club) portrayed here have different relationships (conservationist, geologist, resort developer) to their environment, and they encounter each other on mountain trails, in forests and rapids, sometimes with reserve, sometimes with friendliness, sometimes fighting hard across a philosophical divide. McPhee evenly describes the debates, the differences of opinion, the questions facing us all in our fast developing world and finite resources as the men wrestle with questions of man versus wilderness.)

HISTORICAL FICTION:

The Frozen River, Ariel Lawhon (Historical mystery based on the real-life diary entries of Martha Ballard, an 18th-century midwife who found herself at the center of a murder trial. Martha was privy to secrets of the town’s women as she attended their births, keep journals of her days, and when a body was discovered dead in the frozen river, she did medical investigation. The judge and dead man had been accused of rape by the preacher’s wife. Fascinating “inspired by” true events, weaving in life in a long, hard winter in Maine with births and deaths.)

Human Acts, Han Kang (Nobel Prize laureate. Amid a violent student pro-democracy uprising in South Korea in 1980, a young boy named Dong-ho is shockingly killed (the Gwangju Massacre). The story of this tragic episode unfolds in a sequence of interconnected chapters as the victims and the bereaved encounter suppression, denial, and the echoing agony of the massacre. From Dong-ho’s best friend who meets his own fateful end; to an editor struggling against censorship; to a prisoner and a factory worker, each suffering from traumatic memories; and to Dong-ho’s own grief-stricken mother; and through their collective heartbreak and acts of hope is the tale of a brutalized people in search of a voice. Poetic, vividly descriptive of unprovoked acts of extreme violence.)

We Do Not Part, Han Kang (Booker Prize; Pulitzer Prize. The Guardian: “We Do Not Part” takes on the lasting devastation of the violent suppression of the Jeju uprising of 1948 and 1949. Between 1947 and 1954 on Jeju, an idyllic subtropical island off the coast of South Korea, at least 30,000 people were killed in mostly government-perpetrated atrocities, which involved gang rape, infanticide and mass executions of civilians. Han’s novel is narrated by Kyungha, a historian and writer living in Seoul who suffers from chronic pain so bad she has contemplated suicide. She and her friend Inseon, a filmmaker turned carpenter from Jeju, have long planned to collaborate on an ambitious project, part installation and part documentary feature, incorporating blackened logs in a landscape as a memorial to the victims of violence. The cut-down trees stand in for cut-down people — in Kyungha’s dream, they are “torsos” — just as the women’s failure to complete the project stands in for the impossibility of ever fully reckoning with the brutality of power. Early in the book Inseon summons Kyungha to a hospital in Seoul where she is being treated — in a repetitive and excruciating way — for a grievous hand injury incurred in her carpentry studio. Having left her home in a rush, Inseon tasks her friend with an urgent journey to Jeju, about 300 miles away, to save a pet bird she fears will starve to death while she lies in her hospital bed. But a dangerous snowstorm hampers the quixotic bird-rescue expedition, and Kyungha is left isolated in the dreamlike surroundings of Inseon’s compound, where she eventually uncovers evidence of her friend’s obsessive investigation into the family’s tragic losses in the time of the massacres. On the site of this family home in Jeju, the buried appear to rise again, their shadows flitting over the walls; dead and absent people and birds are intermittently present, and the distinction between dead and living grows fuzzy. The past leaks disjointedly into the present as the novel layers witnessing upon witnessing — a handing down of memory between generations, from one damaged woman to another. Poetic, dream-like, past and present intertwined, the novel is unique but a testament to the unspeakable horrors of the past and the brutality of war.)

Greek Lessons, Han Kang (In a classroom in Seoul, a young woman watches her Greek language teacher at the blackboard. She tries to speak but has lost her voice. Her teacher finds himself drawn to the silent woman while day by day he is losing his sight. Soon the two discover a deeper pain binds them together. For her, in the space of just a few months, she has lost both her mother and the custody battle for her nine-year-old son. For him, it’s the pain of growing up between Korea and Germany, being torn between two cultures and languages, and the fear of losing his independence. The fading light of a man losing his vision meeting the silence of a woman who has lost her language brings them together in a unique way, quiet, tender, language said and unsaid.)

Grace, a Novel, Paul Lynch (The Irish potato famine (1845-1852), a story of suffering and survival. Grace, hair shorn, dressed as a boy, is forced from the family’s home to find a way to make some money. Her brother, Colly, follows her, eventually drowning but still in her head, a ghost, a reminder of home. A journey through hell, the poverty, the haves and have-nots, the despair, the hunger, always the hunger, families torn apart, spirits and ghosts and demons, hauntings, and surrender. Lynch’s writing is replete with lyrical prose while breaking one’s heart with his descriptions of the land, ravished, the people, becoming unlike themselves, the fear, the starvation, the becoming less human. “She left a wee boy and came back a beautiful woman.” Coming of age, wandering, spiritual, orphan, Lynch’s narrative is brilliant.)

The Consequence of Anna, Kate Birkin (1930, Esperance, Australia, based on a real story: Anna May Shahan, a childlike woman suffering from undiagnosed mental illness, always gets her way. Her loyal husband James, tricked into marriage and loathing his life on their remote sheep station in the Outback, longs for something more. Anna’s English cousin Lottie arrives, and everyone’s world changes. Based on true events, a saga about family, love, mental illness (schizophrenia, dissociative identity disorder. Asperger’s Syndrome), betrayal, and forgiveness. The book was fascinating but much too long, with repetitive chapters, language that didn’t always “match” the setting, the ending tied up too many pieces, unrealistic. Loved the Australian Outback descriptions).

Clear, a Novel, Carys Davies (John Ferguson, a Scottish minister, is set on mission to remove Ivar, a man from his land in northern Ireland, but mishaps change the course of his task. Unfolding during the final stages of the infamous Scottish Clearances—a period of the 19th century which saw whole communities of the rural poor driven off the land in a relentless program of forced evictions—this singular novel explores what binds us together in the face of insurmountable difference, the way history shapes our deepest convictions, and how the human spirit can endure despite all odds. Unexpected but beautiful ending.)

Mont Saint Michel and Chartres, Henry Adams (1905: Adam’s meditative journey across time and space in his medieval imagination of thirteenth century France, where he discovers and studies the architecture, sculpture, and stained glass of Norman-style Mont Saint Michel and gothic Chartres. Significant cathedral architecture occurred in France during 1100-1200s: Adams imagines a tourist traveling through France, studying the architecture, learning the various architectural styles, attributing some to the Virgin Mother/Queen/Empress, especially Chartres, which is very feminine in its build, compared to other less balanced or stunning buildings. In fact, he is writing more of his worldview and perspective on those times, as opposed to pure history. Dense but light-hearted in places, a formidable work. Adams wrote: “All these schools had individual character, and all have charm; but we have set out to go from Mont Saint Michel to Chartres in three centuries, the eleventh, the twelfth, and the thirteen, trying to get, on the way, not technical knowledge; not correct views on either history, art, or religion; not anything that can possibly be useful or instructive; but only a sense of what those centuries had to say, and a sympathy with their ways of saying it.”)

Une Vie: A Woman’s Life, Guy de Maupassant (1883: Maupassant’s first novel about a young woman who leaves her innocent convent school life to return to family’s chateau in Normandy, dreamy, passive, hoping for a love-filled life. Instead, she meets Julien, falls in love, marries, and shortly thereafter, he presents his true self, philanderer, hording Jeanne’s money, economizes, treating her almost as if a servant. The story of a life, without aim, with exaggerated hurts, calmed by the beauty of the natural world, but unable to take control of her life or exhibit any agency. The descriptions of nature, the countryside, the ocean, are exquisite but the characters frustrating and stereotypic.)

Isola, Allegra Goodwin (Based on a true event, in early 1500’s France, Marguerite de la Roque, a young girl whose parents have died and whose guardian has spent all her wealth, is forced to sail to New France (Canada) with her guardian (Roderval) and ship mates, in his quest to colonize what would be Quebec in the name of the King of France. Marguerite falls in love with guardian’s secretary (Augustine), is cast ashore on tiny granite island with her lover and her nanny (Damienne). What follows is a tale of suffering, love, survival, faith, acceptance.)

The Great Divide: A Historical Novel of the Panama Canal, Christina Henriquez (The construction of the Panama Canal was one of the modern engineering feats of the twentieth century. It came with a cost to those living in Panama, seeing the destruction and tearing apart of their country, the hundreds of lives lost in the “Big Mouth,” as they called the huge excavation across their country, destroying towns, forests, etc., even as it brought progress and jobs. “The Great Divide” explores the lives of the laborers, fishmongers, journalists, protesters, doctors, and soothsayers who lived alongside the construction of the Canal – those rarely acknowledged by history even as they carved out its course. Individual stories, Ada, the cast-away from Barbados who needs money for her ill sister, Francisco, the fisherman, and his son, Omar, who worked on the canal to combat his loneliness, the Oswalds from Tennessee who came to combat malaria, Valentina and her sister, Renate, whose home was being relocated to make way for the canal, each has a story that is universal.)

Go As A River, Shelley Read (Using the backdrop of the building of the Blue Mesa Dam by destroying small towns, including Iola, along the Gunnison River valley, in mid-century Colorado, this is a heart-breaking coming-of-age story of Victoria and Wilson Moon. The two have only a small time together before tragedy pulls them apart, but their love allows Victoria to become resilient, to be brave, to be independent, to live on and with the land (so beautifully narrated throughout the book), and to “go as a river,” to flow with events, allowing life to finally give her what she most needs. Family, loss, love, a sense of place, of home, melded together into a story of heartache and hope.)

The Club: Where American Women Artists Found Refuge in Belle Époque Paris, Jennifer Dasal (In the United States in the 1800s and later, women were barred from attending the best art academies and denied admission to life-drawing classes with nude models—a basic and essential element of an artist’s education. To fill that gap in young women’s art education, many traveled to France, the epicenter of art and more welcoming to women artists. Two American women established the “American Girls Club,” as it was commonly known, a residence for young American artists studying in Paris during the Belle Époque, 1890s-1914, a home away from home, a safe and secure place for these young girls to experience life in Paris while honing their craft as artists. From letters, journals, newspaper articles, Dasal writes of the beginnings of the Club, the importance for many young women to have a place to gather, to socialize, to engage with others similarly situated, to show their art, to ease the fears of their parents. The book sheds light on the various art schools, art movements, and importance of Paris as the center of art at that time. Well-researched, especially the perspectives of the residents, why women artists aren’t more well-known, etc.)

The Great Believers, Rebecca Makkai (The Great Believers is story of a group of friends and their emotional journey through the 1980s AIDS crisis in Chicago and its effects on the contemporary lives of survivors. In 1985-86, Yale is development director at art gallery at Northwestern University and is beginning work on a collection of paintings from 1920s Paris artists (a subplot of the book, authenticating art from an elderly woman who had been a model for some of the sketches and paintings). The AIDS epidemic soon consumes Yale and his friends, often cared for by Fiona, the sister of Nico, one of the young men killed by the ravaging disease. Thirty years later, Fiona is in Paris trying to find her estranged daughter when she realizes that she, too, is a survivor of the early days of AIDS, sacrificing her own life, marriage, and daughter in caring for her sick and dying friends. A powerful meditation on the gift of friendship and love.)

The Book of Days, Francesca Kay (Tudor England, 1546. A woman keeps track of the days as her dying husband focuses on the chapel he is having built to his immortal soul. As the chapel takes shape, the outside world begins to intrude, old ways replaced by new, villagers sensing a new freedom. It is the time of the death of King Henry and his young son as new king, England breaking away from Rome, the barring of idols, of saints, where prayer and religious song is banned. Almost poetry, the mother then widow keeps track of the changes, of her friends, of their deaths, of her heartaches. Quite beautiful and touching.)

The Land in Winter, Andrew Miller (1962: Doctor Eric Parry and his wife Irene, and new farmer, Bill and his wife Rita, led separate lives but are becoming acquainted, as neighbors living on either side of a large meadow.. Eric has a lover, unbeknownst to Irene while Bill is struggling with his small farm. Both women are pregnant with their first child and as they spend time together, even though they are from two very different social classes, they feel a connection. As the couples head into the coldest winter in decades in England, relationships change, secrets are revealed, where does one go when housebound? Shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2025, Miller embraces the minutiae of life even while large questions loom.)

FICTION:

Barbara Kingsolver:

Flight Behavior, Barbara Kingsolver (Dellarobia, a poor, uneducated farmer’s wife discovers a forest filled with orange monarch butterflies in the forests of Appalachia, far from their typical migration pattern of wintering in Mexico. She is changed by their shimmering beauty, almost a spiritual transformation, and questions how they came to be. Her family finds religion and God in their being, while a scientist comes to study the phenomenon, focused on climate change and why the migration pattern has changed. Over the course of the winter months studying the butterflies, Dellarobia’s life is changed, hard decisions made, coming into her own. The book crafts local characters with their long-held beliefs, idiosyncrasies, trying to make do, living tough lives amidst a rapidly evolving world.)

Pigs In Heaven, Barbara Kingsolver (Picking up where her modern classic The Bean Trees left off, Barbara Kingsolver’s bestselling Pigs in Heaven continues the tale of Turtle and Taylor Greer, a Native American girl and her adoptive mother who have settled in Tucson, Arizona, as they both try to overcome their difficult pasts. Taking place three years after The Bean Trees, Taylor is now dating a musician named Jax and has officially adopted Turtle. But when a lawyer for the Cherokee Nation begins to investigate the adoption their new life together begins to crumble. Depicting the clash between fierce family love and tribal law, poverty and means, abandonment and belonging, Pigs in Heaven is a morally wrenching, gently humorous work of fiction that speaks equally to the head and the heart.)

Colum McCann:

Twist, a Novel, Colum McCann (Author of “Let the Great World Spin” and “Apeirogon”. “Everything gets fixed, and we all stay broken.” Anthony Fennell, an Irish journalist and playwright, is assigned to cover the underwater cables that carry the world’s information. The sum of human existence—words, images, transactions, memes, voices, viruses—travels through the tiny fiber-optic tubes. But sometimes the tubes break, at an unfathomable depths. When their ship is sent up the coast to repair a series of major underwater breaks, both Fennell and fellow Irishman Conway, responsible for the repairs, learn that the very cables they seek to fix carry the news that may cause their lives to unravel. At sea, they are forced to confront the most elemental questions of life, love, absence, belonging, and the perils of our severed connections. Can we, in our fractured world, reweave ourselves out of the thin, broken threads of our pasts? Can the ruptured things awaken us from our despair? McCann’s descriptions are lyrical and vivid, a joy to read with many questions to ponder.)

Song Dogs, Colum McCann (Songdogs is Colum McCann’s debut novel, a story about memory, identity, and family, told through the eyes of 23-year-old Conor Lyons, who returns to his ailing father in Ireland after years away. The narrative weaves together Conor’s present-day quest to understand his past with flashbacks to his rootless father’s life as a photographer in Spain, Mexico, and America, and the story of how he met and lost Conor’s mother. Lyrical and poetic with underlying melancholy, a quiet, meditative book about heartbreak (how does Conor, the son, reconcile his love for his father with his father’s relationship with his mother) and promise, the seeking of his mother, lost forever.)

Amity Gaige:

Schroder, Amity Gaige (Attending a New England summer camp as an adolescent, young Erik Schroder – a first generation East German immigrant – adopts a new name and a new persona – Eric Kennedy – in the hopes that it will help him fit in. This fateful white lie will set him on an improbable and ultimately tragic course. Schroder relates the story of Eric’s urgent escape years later through the New England countryside with his six-year-old daughter, Meadow, in an attempt to outrun the authorities amidst a heated custody battle with his wife, who will soon discover that her husband is not who he says he is. From a correctional facility, Eric surveys the course of his life in order to understand – and maybe even explain – his behavior; the painful separation from his mother in childhood; a harrowing escape to America with his taciturn father; a romance that withered under a shadow of lies; and his proudest moments and greatest regrets as a flawed but loving father. The question, is how far will we go for love, whether Erik’s father in escaping from East Germany or Erik, escaping his childhood and then, with his daughter, his wife.)

Heartwood, a Novel, Amity Gaige (A nurse, Valerie Gillis, goes missing on the Appalachian Trail in Maine. Lt. Bev Milleris the veteran game warden in charge of the search for Valerie. Lena Kucharski is a 76-year-old retired scientist who lives at assisted living center, spending her days foraging. Each woman’s relationship with her mother is the center of their individual stories, as the search for Valerie extends into days beyond what normally is considered the time period in which a lost hiker will still be alive. Valerie’s chapters are presented through “love letters” to her mother, where we learn of her anxiety and fears, but not really depth of character. Lt. Bev battles with being a lone woman in her profession, still trying to prove herself to her mother. Lena is the fascinating sleuth, estranged from her daughter. The search descriptions are fascinating, the whys and hows of thru-hikers as diverse as those hiking, the Maine woods terrifying and immersive. The thriller builds to an unexpected resolution. Very engaging!)

Sue Monk Kidd:

The Mermaid Chair, Sue Monk Kidd (Forty-two-year old Jessie is called back to the small South Carolina where she grew up to attend to her somewhat estranged mother, Nelle, who has severed, intentionally, her right digit finger. In some respects, Jessie is fleeing her picture-perfect marriage to Hugh, feeling a vagueness of discontent, of having lost herself within the marriage. On the island, she falls in love with a Benedictine Monk while failing at helping her mother, who has secrets related to the death of Jessie’s father on his fishing board 30 years earlier. The island is itself a character, with its wonderfully descriptive marshes, egrets, water channels, wind, sand, smells, and sounds. The Mermaid Chair is a book that embraces the sensual pull of the mermaid and the divine pull of the saint, the commitment to oneself and the commitment to a relationship-and their ability to thrive simultaneously in every woman’s soul. Kidd’s candid and redemptive portrayal of a woman lost in the “smallest spaces” of her life ultimately becomes both an affirmation of ordinary married love and the sacredness of always saving a part of your soul for yourself.)

The Secret Life of Bees, Sue Monk Kidd (Set in rural South Carolina in 1964, the book is the story of Lily Owens, whose life has been framed by the death of her mother when Lily was four (and for which she believes is responsible). Raised by Rosaleen, a black woman, and abused at the hands of her father, Lily breaks Rosaleen out of prison after she was beaten by three racist men. They escape to Tiburon, SC, the one place where Lily believes she may learn about her mother. There, they are welcomed into the home of three sisters, beekeepers, and the Black Madonna statue, and their loving group of women friends. Lily is introduced to the world of beekeeping, honey, and the mother Mary figure. Beautifully written, heart-warming, a family created by love and care, this book tells of the power of women and love.)

Kiran Desai:

The Inheritance of Loss, Kiran Desai (Man Booker Prize 2006. Although it focuses on the fate of a few powerless individuals (the retired Indian judge, his granddaughter, Sai, his cook, the cook’s son, Biju, an illegal immigrant living in New York City, and Sai’s tutor/boyfriend, Gyan, who becomes a dissident), Kiran Desai’s novel explores, with intimacy and insight, most every contemporary international issue: globalization, multiculturalism, economic inequality, fundamentalism, and terrorist violence. Set in the Indian side of the Himalayan mountains in the mid-1980’s, it describes battles among and between countries, tribes, neighbors, extreme poverty, the Indian caste system, without necessarily hope of a more equalitarian world. Vivid characters, sweeping reach, the land as much of as character as the people.)

The Loneliness of Sonia and Sonny, A Novel, Keran Desai (The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny is the sweeping tale of two young people navigating the many forces that shape their lives: country, class, race, history, and the complicated bonds that link one generation to the next. A love story, a family saga, and a rich novel of ideas, it is the most ambitious and accomplished work yet by one of our greatest novelists.)

Others:

What We Can Know, a Novel, Ian McEwan (Civilization as we know it ends; the droughts, the global wars, the climate change with rising oceans and melting glaciers, the loss of privacy due to the internet and social media, the twenty-first century no longer progress. A pair of scholars in 2120, risking death from roving predatory gangs, travel across what’s left of England (now an archipelago of islands, disconnected from most of the world) in search of a long-lost, epoch-making poem titled “A Corona for Vivien.” They are the last, it seems, historians alive. It’s about what biographers owe their subjects. It’s about the nature of history. It’s about letters, journals, emails and the other things we leave behind. It makes one nostalgic for the present, given how the world has changed 100 years later. There is murder, a near kidnapping, a child hideously dead of neglect, multiple revenge plots, buried treasure and literary arson. No one is a moral paragon, as our primary protagonists betray, envy, steal, and see the world as they want it to be, not necessarily as it now is. Brilliant, funny, contemplative, one of McEwan’s best works.)

*The Inhabited Woman, Gioconda Belli (Lavinia is The Inhabited Woman: accomplished, independent, and fiercely modern Nicaraguan woman. She is sheltered and self-involved, until the spirit of Itza, an Indian woman warrior who fought against the Spanish conquistadors centuries earlier, enters her being, then she dares to join a revolutionary movement against a violent dictator (Somoza) and—through the power of love—finds the courage to act. Both woman in their times share the struggle of trying to find their place in a world defined by and dominated by men, amidst the ongoing struggle for freedom and equality. Magical realism, descriptive, “coming-of-age” story in certain respects as these women find their own voices among male-dominated society, highly recommend.)

Moon Tiger, Penelope Lively (1987 Booker Prize winner: Claudia, 72 and in hospital, was historian, war correspondent, lover, mother, sister, elusive, beautiful, independent. She declares to her nurse that she is going to write a history of the world: her world, her memories intertwined with time as correspondent during World War II, an especially poignant love affair. “Moon Tiger” (meaning the symbolic march of time, the fallibility of human impressions and the fragility of memory) explores the subjective nature of memory, the difference between lived and linear time, and the way global history overlaps with personal history. Author writes on different planes, Claudia internally and externally, her experiences seen from her perspective and that of others, her life played out before her eyes. Unique style, compelling.)

Time of the Child, Niall Williams (Doctor Jack Troy was born and raised in Faha, a small town in Ireland. His responsibilities as doctor have always set him apart from the town. His eldest daughter, Ronnie, has grown up in her father’s shadow, and remains there, having missed one chance at love – and passed up another offer of marriage from an unsuitable man. 1962, as the town readies itself for Christmas, Ronnie and Doctor Troy’s lives are turned upside down when a baby is left in their care—with whom Ronnie immediately falls in love—and which he father wants to endure even as church and state and community reputation are against them. As the winter passes, the father and daughter’s lives, the understanding of their family, and their role in their community are changed forever—humanity prevails.)

The Granddaughter, Bernard Schlink (After the sudden death of his wife, Birgit, Kaspar discovers the price she paid years earlier when she fled East Germany to join him in West Germany: she had given up her baby. Kaspar closes up his bookshop in present day Berlin and sets off to find her lost child in the east. His search leads him to a rural community of neo-Nazis, intent on reclaiming and settling ancestral lands to the East. Among them, Kaspar encounters Svenja, his wife’s daughter, along with her red-haired, slouching, fifteen-year-old daughter, SIgrun. His granddaughter? Their worlds could not be more different— an ideological gulf of mistrust yawns between them— but he is determined to accept her as his own. The novel probes the past’s role in contemporary life, transporting us from the divided Germany of the 1960s to modern day Australia, and asking what unites or separates us.)

Intermezzo, Sally Rooney (“Intermezzo” is about two brothers, Peter, a successful barrister in Dublin, and Ivan, who is shyer, geekier, 10 years younger, wears ceramic braces and plays competitive chess. They are mourning the death of their father with lingering bitterness between them. It is also a love story, Peter and Sylvia/Naomi, and Ivan/Margaret. What is love, how is it defined, felt, conveyed, filial love, romantic/platonic love, obligatory. Interesting writing style between chapters about Peter (lack of verbs; staccato like) and those about Ivan (organized, cautious), conveying their different personalities.)

My Friends: A Novel, Hisham Matar (Three young Libyan men (Khaled, the narrator, Mustafa, and Hosam), in exile in London, become friends, become estranged, come together again, part for ever. Their story reaches back into their childhoods, but the main narrative begins in 1984, the year that officials inside the Libyan embassy in London’s St James’s Square fired a machine gun into a crowd of unarmed protesters. Two of the friends are injured, which changes the trajectories of their lives, unable to go home, to call family, to relate what happened. This is a book about exile and violence and grief, but it is above all – as the title tells us – a study in friendship. Khaled loves his two friends, although he doesn’t always like them. He observes their rivalries. He is hurt when they exclude him. He is often self-deluded, but the frankness with which he thinks, as he walks and remembers, about what they have meant to him, gives this quietly spoken book a slow-growing but impressive force. “Friends,” says Hosam. “What a word. Most use it about those they hardly know. When it is a wondrous thing.”)

The Trees, Percival Everett (A series of brutal murders are linked by the presence at each crime scene of a second dead body, a Black man who resembles Emmett Till, a young Black boy lynched during the Civil Rights Movement 60 years before. The detectives discover similar gruesome murders around the country, seeking answers from a local root doctor, who has been documenting lynching in the US for years. The Trees combines an unnerving murder mystery with the powerful condemnation of racism and police violence, causing panic throughout the country. A compelling read with its unique, unlikely protagonists and southern mysticism. “Rise.”)

*The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Milan Kundera (Czech revolution in 1960s, Tomas, a surgeon, Tereza, eventually his wife, Sabina, artist and one of Tomas’s lovers, Franz, Sabins’s lover, and Karenin, Tomas & Tereza’s dog. Multiple story lines—political, personal, sexual; psychological—mind and body, which takes precedence; philosophical–weight and lightness (the unbearable lightness of living just one life, no eternal return, which would give our lives weight, heft, make them bearable); narrator as part of story (which interrupts flow of novel or makes it less a traditional novel, by his creation of characters for which author doesn’t have preconceived notions of how they might act); interiority of characters, lies, betrayals, narcissistic; political power of state (totalitarianism kitsch) is unachieved utopia,no no agency of individuals; rules of revolution, how does one respond, who does one trust. What is this one life that we live?)

*The Professor’s House, Willa Cather (The Professor’s House (1925) follows Godfrey St. Peter as he experiences a change in his domestic life, his family moving to a new home. While the rest of his family is excited about the move, St. Peter can’t seem to detach himself from the old house. It contains his study where he does all of his writing for his historical books, but it also is the place where his favorite student, Tom Outland, became acquainted with the St. Peters. As St. Peter’s family becomes increasingly materialistic, the professor grows increasingly detached, questioning what truly matters. A split occurs between his life in his old study and the life that he is expected to lead with his family. St. Peter must determine who he wants to be in his old age. The middle section is almost a separate book, about Tom Outland when he is spending time in southwest, discovering its unique beauty. It is this section that Cather’s writing shines, describing the Southwest, the light, the canyons, the ancient tribal village.)

Dream Count, A Novel, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (The author of “Americanah” weaves the tale of four Nigerian women (Chia, Zikora, Omelogor, and Kadi [based on true story of maid who accused Dominique Strauss-Kahn of rape in NYC hotel), friends and cousins, becoming adults, learning the ways of being friends, of breaking apart from family, of life in America and Nigeria, wrestling with self-knowledge and self-care, trying to understand how one truly knows one-self, let alone another person. Powerful and evocative exploration of personal and societal struggles of women. The book is deeply infused with empathy and compassion. Adichie’s mastery of narrative shines through as she weaves together themes of identity, culture, and ambition, set against the backdrop of contemporary African life. Adichie says novel is really about her mother, her grief at her death, the regrets.)

Rebecca, Daphne du Maurier (Written in 1938: “Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.” The novel begins in Monte Carlo, where our unnamed heroine is swept off her feet by the dashing widower, Maxim de Winter, and his sudden proposal of marriage. Orphaned and working as a lady’s maid, she can barely believe her luck. It is only when they arrive at Manderley, his massive country estate, that she realizes how large a shadow his late wife, Rebecca, casts over their lives–presenting her with a lingering evil that threatens to destroy their marriage from beyond the grave. The narrator is a dreamer, wondering about Rebecca, the staff, the malevolent house-manager, Mrs. Danvers (who is grief-stricken by the death of Rebecca and believes the second Mrs. de Winter will never replace her). Rebecca was beautiful, bewitching but controlling, evil. Manderley is one of the novel’s protagonists with its beauty, its size, the hold on Maxim. A murder mystery, a romantic tale, a gothic novel with the weather and house and the sea having huge impacts on the events. Fascinating, enduring novel, with its questions of sexuality, gender, patriarchy, merging of dreams with reality.)

My Brilliant Life, Asran Kim (Sixteen-year-old Han Areum has progeria, a rare, progressive, incurable genetic disease that causes people to age unnaturally. He is narrator, now sixteen, the age his parents were when he was born in a rural village in Korea. His disease has progressed to where he looks like eighty, has significant organ failure, and doctors want him in hospital full time. Areum is mostly self-taught and wants to write a story about his parents—what it means to be a parent, what it means to be a child, and what might a child think who is aging significantly faster than his parents. “My Brilliant Life” is a heart-warming story of a youth refusing to see his life as a waste and making the most of the little time he has available to him. And perhaps that’s what most readers will take away from the experience – the idea that every life can be brilliant if you only look at it from the right angle.)

Yellowface, R.F. Kuang (June Hayward and Athena Lui were college acquaintances, now authors, Athena a literary darling while June is another wannabee writer. When Athena dies in a tragic accident, June steals her just-finished masterpiece about the Chinese labor force in France during World War I. June becomes Juniper Song, the novel becomes a best-seller, and Juniper reaps the benefits of Athena’s ideas—until a vicious social media campaign questions the legitimacy of Juniper’s work, her cultural appropriation, her perceived racism. An insightful look into the competitive world of authors and publishing with the loneliness and terror of vicious social media attacks. Kuang’s first person narrative is compelling, questioning, ‘what would you do?’ although Juniper/June is not necessarily a very likable character.)

Headshot, a Novel, Ruth Bullwinkel (Eight teenage girls gather at a gym in Reno for the semi-finals of an under-eighteen girls’ boxing competition. Each boxer has her story of “why boxing”—family legacy, recognition, loneliness. Each story is told as the girl is boxing, with ruminations about the past, the present, and who she might be in the future. Boxing may not even be remembered, but in the present, it brings success, self-confidence, inner strength, a purpose. NY Times: “This is kinetic writing, but it would mean little without this novel’s undertow of human feeling and the rapt attention it pays to life’s bottom dogs, young women who are short on sophistication but long on motivation.”)

Dear Edward, Ann Napolitano (A twelve-year-old boy, Edward, is sole survivor of a plane crash that kills 191 people, including his parents and his brother, Jordan, with whom he was incredibly close. Inspired by an airplane crash where a small boy was the sole survivor, Napolitano carefully and thoughtfully, with warmth and heart, tells Edward’s post-crash story, living with his aunt and uncle, finding a friend in Shay, healing his physical wounds while the emotional wounds continue to tear him apart. The kindness of his family and friends, a school principal, allow him to slowly realize his grief. The discovery of letters to him from the families and friends of the plane’s victims shake him to the core but give him relief. The chapters are intermixed—passengers on the plane before the crash and Edward’s life—give perspective and substance to a beautifully written story.)

*Plato’s Symposium, Plato (The Symposium is a Socratic dialogue by Plato, dated c. 385 – 370 BC. It depicts a friendly contest of extemporaneous speeches given by a group of notable Athenian men attending a banquet. The men include the philosopher Socrates, the general and statesman Alcibiades, and the comic playwright Aristophanes. The panegyrics are to be given in praise of Eros, the god of love and sex. In the Symposium, Eros is recognized both as erotic lover and as a phenomenon capable of inspiring courage, valor, great deeds and works, and vanquishing man’s natural fear of death. It is seen as transcending its earthly origins and attaining spiritual heights. The extraordinary elevation of the concept of love raises a question of whether some of the most extreme extents of meaning might be intended as humor or farce. Eros is almost always translated as “love,” and the English word has its own varieties and ambiguities that provide additional challenges to the effort to understand the Eros of ancient Athens. The philosophers especially recognize homosexual love between a man (the lover) and a young boy (the beloved) and much of the dialogue centers on these concepts.)

*The Quiet American, Graham Greene (Narrated in the first person by British journalist Thomas Fowler (an unreliable and jaded narrator), the novel depicts the breakdown of French colonialism in Vietnam, and early American involvement in the Vietnam War. A subplot concerns a love triangle between Fowler, Alden Pyle (an “innocent”, perhaps CIA agent, who believes in a Third Force to stabilize the country), and Phuong (a young Vietnamese woman). The novel implicitly questions the foundations of growing American involvement in Vietnam in the 1950s, exploring the subject through links among its three main characters: Fowler, Pyle and Phuong.)

The Beauty of Your Face, Sahar Mustafah (A profound and poignant exploration of one woman’s life in a nation at odds with its ideals.Afaf Rahman, the daughter of Palestinian immigrants, is the principal of Nurrideen School for Girls, a Muslim school in the Chicago suburbs. One morning, a shooter―radicalized by the online alt-right―attacks the school. As Afaf listens to his terrifying progress, we are swept back through her memories: the bigotry she faced as a child, her mother’s dreams of returning to Palestine, and the devastating disappearance of her older sister that tore her family apart. Still, there is the sweetness of the music from her father’s oud, and the hope and community Afaf finally finds in Islam—especially through the women with whom she forms a community. Why does one’s religious beliefs invoke such hatred in others? Unanswerable, perhaps.)

Fencing with the King: a Novel, Diana Abu Jaber (A story of family, heritage, legacy set in the 1990s with a gathering for the king of Jordan’s 60th birthday. The story of three brothers, Farouq, Hadez (advisor to the King), and Gabe, their father’s favorite who comes from US to fence with the king on his celebration day. Amani, Gabe’s daughter, joins her father for the month-long celebrations, on a quest to learn more of her grandmother and her family’s journey forty years earlier as refugees to the area of Jordan, Muslims, Christians, and atheists. A story of place, of family history, of secrets, set in the turmoil of the Middle East. Well-drawn characters, bits of important history, questions of who one is with and without family, those we leave behind, exquisite descriptions of the land and sky and stars.)

The River We Remember, a Novel, William Kent Krueger (On Memorial Day, as the people of Jewel, Minnesota gather to remember and honor the sacrifice of so many sons in the wars of the past, the half-clothed body of wealthy landowner Jimmy Quinn is found floating in the Alabaster River, dead from a shotgun blast. Investigation of the murder falls to Sheriff Brody Dern, a highly decorated war hero who still carries the physical and emotional scars from his military service. Even before Dern has the results of the autopsy, vicious rumors begin to circulate that the killer must be Noah Bluestone, a Native American WWII veteran who has recently returned to Jewel with a Japanese wife. As suspicions and accusations mount and the town teeters on the edge of more violence, Dern struggles not only to find the truth of Quinn’s murder but also put to rest the demons from his own past. Both a complex, spellbinding mystery and a masterful portrait of mid-century American life, The River We Remember is an unflinching look at the wounds left by the wars we fight abroad and at home, a moving exploration of the ways in which we seek to heal, and a testament to the enduring power of the stories we tell about the places we call home. Krueger’s description of place and of home, why we stay, why we leave, why we return, gathers the emotions, beauty, and draw of the places each of us call home.)

The Original Daughter, Jemimah Wei (“The Original Daughter” lays bare the claustrophobia of familial love, the ache of unfulfilled dreams and the costs of repressed emotion, through the earnest and often knotty relationship between two sisters growing up in Singapore in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Genevieve, the “original” daughter, and Arin, the daughter of Gen’s father’s half-brother—a betrayal in itself–are inseparable as children; as adults they lead different paths with different successes that cause friction, rupture, and competition. Love lost, betrayed, hurt, broken, all the ways in which we don’t realize how we can hurt people and be hurt by them, all in the name of love or family or friendships.)

The Emperor of Gladness, Ocean Vuong (One late summer evening in the dying town of East Gladness, Connecticut, nineteen-year-old Hai stands on the edge of a bridge in pelting rain, ready to jump, when he hears someone shout across the river. The voice belongs to Grazina, an elderly widow succumbing to dementia, who convinces him to take another path. Bereft and out of options, he quickly becomes her caretaker. Over the course of the year, the unlikely pair develops a life-altering bond, one built on empathy, spiritual reckoning, and heartbreak, with the power to transform Hai’s relationship to himself, his family, and a community on the brink of despair. Poetic, lyrical, with linguistic magic, Vuong has imbued his characters with tenderness, empathy, and an understanding of those marginalized and forgotten.)

The Reading List, Sara Adams (Elderly widower Mukesh Patel is not thriving after his wife’s death from cancer. He is lonely and tends to be reclusive, unlike his warm, outgoing wife Naina. His grown daughters are hovering over him and treating him like a child. But when he finds one of Naina’s library books and remembers her love of reading, he decides to venture out to the neighborhood library, setting in motion an adventure that gives him a new purpose in life and connects him with the troubled librarian, seventeen-year-old Aleisha, along with several other library patrons. Aleisha has just discovered a reading list of eight books tucked into the back of one of the library books she was putting away. She decides to read the books on the list, and when Mukesh shows up and asks for reading recommendations, she shares the list with him too. Copies of this reading list have been mysteriously found by several others in the community, and their shared reading experience—reflecting the magic, wisdom, and lessons derived from each book—brings them together in the community library in a beautiful way as they all experience the power of reading to expand the mind and the heart. Here’s what was written on these reading lists: “Just in case you need it: To Kill a Mockingbird, Rebecca, The Kite Runner, Life of Pi, Pride and Prejudice, Little Women, Beloved, A Suitable Boy”)

This Great Big Beautiful Life, Emily Henry (Two writers, Hayden and Alice, are competing to write the biography of Margaret Ives, a wealthy, popular, then secluded woman. Their budding romance and Margaret not telling the truth of her story, with the potential authors not able to discuss their interviews, is interesting but characters lack depth, Margaret’s story draws on and on, and the “romance” between the two authors seems “filler.” Overall author doesn’t seem to have decided what she wants the book to be.)

Miss Benson’s Beetle, Rachel Joyce (publisher: “She’s going too far to go it alone.” It is 1950. London is still reeling from World War II, and Margery Benson, a schoolteacher and spinster, is trying to get through life, surviving on scraps. One day, she reaches her breaking point, abandoning her job and small existence to set out on an expedition to the other side of the world in search of her childhood obsession: an insect that may or may not exist–the golden beetle of New Caledonia. When she advertises for an assistant to accompany her, the woman she ends up with is the last person she had in mind. Fun-loving Enid Pretty in her tight-fitting pink suit and pom-pom sandals seems to attract trouble wherever she goes. But together these two British women find themselves drawn into a cross-ocean adventure that exceeds all expectations and delivers something neither of them expected to find: the transformative power of friendship.)

The River is Waiting: a Novel, Wally Lamb (Corby Ledbetter is struggling. New fatherhood, the loss of his job, and a growing secret addiction–and an unthinkable tragedy that upends his world, his marriage, his family, and results in his incarceration. Themes of substance abuse/addiction, mental health, incarceration and social injustice, racial inequities, grief and forgiveness. Written from Corby’s perspective, sometimes an unreliable–and an unlikable– narrator, I would have liked more from Emily’s perspective, not Corby’s imagining–and his selfish justification–of the loss and how to move forward.)

Wild, Dark Shore, Charlotte McConaghy (Dominic Salt and his three children (Raff, Fen, Orly) are caretakers on Sweatwater Island, a remote, subantarctic island, where researchers have been storing millions of seeds in an underground seed bank. Rising tides are destroying the island, including the vault, and they must vacate. The island, full of rich flora, extraordinary wildlife and unique climate, including thunderous winds, surging waves and deep cold, will soon be uninhabitable. With only weeks before the navy ship comes to vacate the family and the seeds they can save, unprecedented events happen: a woman washes up on shore, several of the researchers die, the family seems to be breaking apart. A story of the bonds between parent and child, of ghosts and deaths, of unbearable hardships, of mysteries and decisions made and regrets coloring daily life, the story grips.)

A Family Matter, Claire Lynch (1983 England, Dawn, married to Heron with three-year-old daughter, Maggie, falls in love with Hazel, a teacher. At that time in England, lesbian mothers, in particular, were believed to be immoral, horrible influences on their children. Complete separation with no rights to custody or visitation, was often the result of divorce. Maggie lives with her father and until she is forty-three, is not told the truth about her mother, who loved her, who wanted to be in touch with her, who stayed away. A book of untruths, secrets, never meant to harm but to protect, scars left, a different history discovered.)

The Goldfinch, Donna Tartt (2014 Pulitzer Prize winner: Theo, a thirteen-year-old boy, and his mother are caught in a bombing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; the mother dies, Theo survives and in his confusion, takes “The Goldfinch” a priceless work of art by a Dutch painter. The story becomes a kaleidoscope of Theo’s life turned upside down, living for a time with a wealthy NY family, whisked to the outer suburbs of Las Vegas with his drinking, gambling father, becomingfriends with Boris, a Ukrainian boy in similar straits, then ten years of PTSD, missing his mother, drugs, time in New York with Hobie, partner of a man with whom Theo spent a few minutes before his death from the bomb and his niece, Pippa, to the underworld of art thievery, Russian mobs, etc. The New York Times: “Yet always, running through the novel like a power chord that may modulate but never quite dies, is the painting of Fabritius’ goldfinch, which Theo smuggles through his troubled early years — it’s his prize, his guilt and his burden, “this lonely little captive,” “chained to his perch.” Theo is also chained — not just to the painting, but to the memory of his mother and to the unwavering belief that in the end, come what may, art lifts us above ourselves. “The painting,” he observes, “was the still point where it all hinged: dreams and signs, past and future, luck and fate.” … [F]or the most part, “The Goldfinch” is a triumph with a brave theme running through it: art may addict, but art also saves us from “the ungainly sadness of creatures pushing and struggling to live.”)

Glorious Exploits, Ferdia Lennon (On the island of Sicily amid the Peloponnesian War, two Syracusans, the out-of-work potters, Lampo and Gelon, offer to feed the Athenian prisoners being held in a quarry, if they can recite some lines from Euripides. Before long, the two men decide to have the prisoners perform Medea. As opening night approaches, the men realize that staging a play can be as dangerous as fighting a war, with all sorts of risks to life, limb, and friendship. Told in a contemporary Irish voice and as funny as it is deeply moving, Glorious Exploits is an unforgettable ode to the power of art in a time of war, brotherhood in a time of enmity, human will throughout the ages, and perhaps most of all, the power of storytelling.)

The Bright Years, Sarah Damoff (A multigenerational family saga that underscores the ways that the Bright family (Lillian and Ryan, their daughter, Georgette (Jet), Elise, Kendi) tries to navigate and survive addiction, grief, shame and the losses that loving deeply can bring to our lives. Secrets and regrets, forgiveness and grace—all figure in this tender story about love, including what makes a family, (birth, friendship, forgiveness?) in its many forms.)