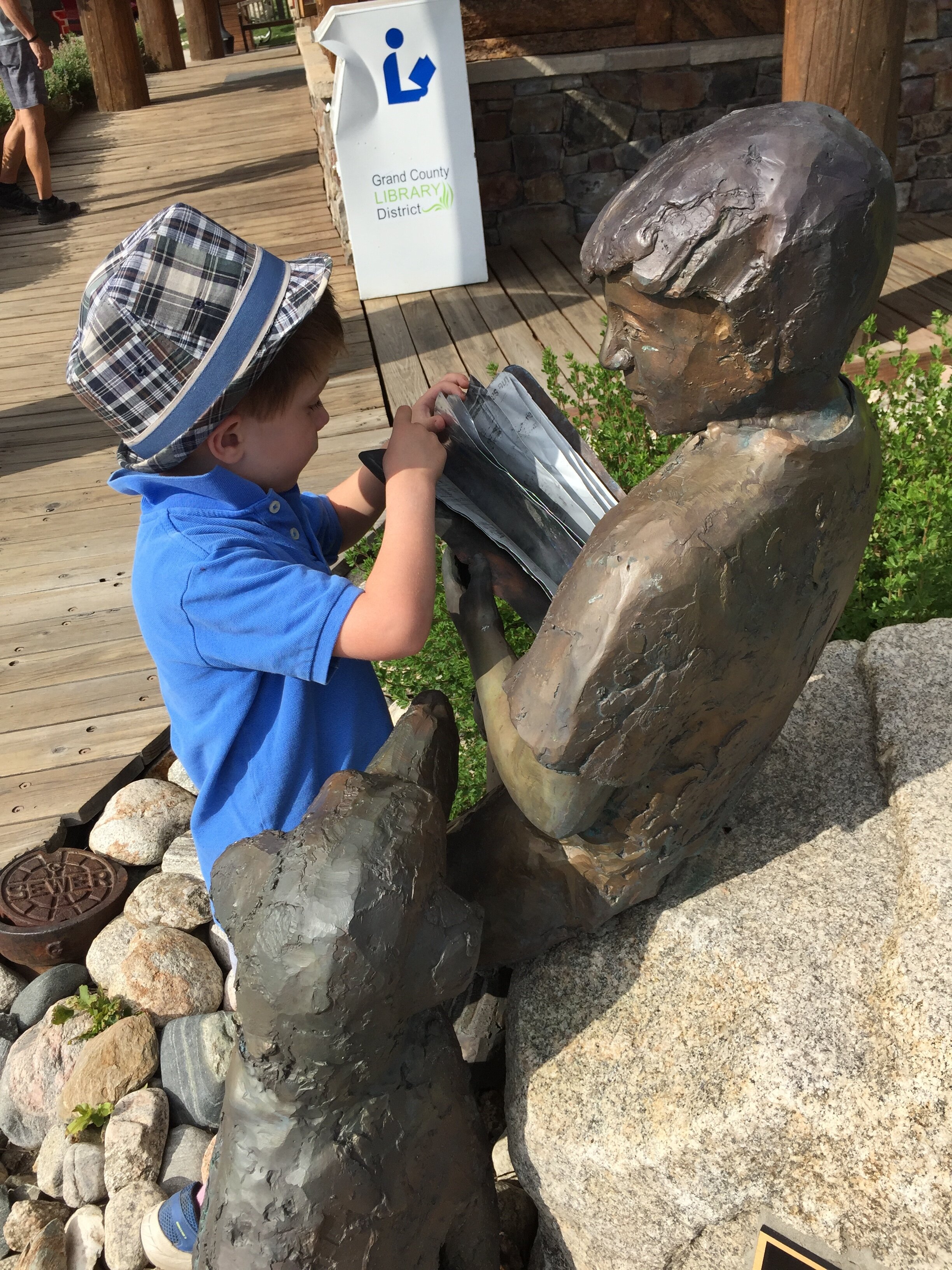

Grand Lake, Colorado, Library

I measure the fleetingness of each year by a compendium of the books I’ve read during that twelve-month period: was there a trend in my reading choices? Did I focus on certain genres? Which books were “must reads” or “highly recommended” by friends and colleagues? Did I read any from “best of books” lists? Which books were disappointments, some that I didn’t finish? How did I make the decision to read a particular book? And then, of course, what about the stack of books still waiting to be opened and discovered (some, unfortunately, hold-overs from last year)?

This year’s list was over-weighted to fiction with several focused categories: classics; stories about race/refugees/immigrants; and historical fiction; and the catch-all miscellaneous group. On the non-fiction side, I favored memoirs along with several deep dives into history, social science and science. Some books were book club recommendations; others were Pulitzer Prize or Booker Man or other award-winning selections; a few were works by long-time favorite authors; and others were the result of a decision to read (or in some cases, re-read) some literary classics.

NONFICTION:

History:

“These Truths, a History of the United States,” by Jill Lepore, a well-known historian, is a massive historical book, based on the objective premise of the founding and creation of the United States: “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” fundamental to the U.S. Constitution. She dissects the history and connected politics of the U.S. from our founding fathers to today’s presidency: have we lived up to the promise (or the belief in the promise) of the creators of the Constitution? In truth, our country was created out of strife, against foreign powers, on the backs of slavery, without an overriding religion, with deep poverty, lack of education, and inequality. She challenges our elemental understanding of our history, asking the hard questions, uncovering uncomfortable evidence, questioning all sides, shedding our political system and propaganda and polling to better understand where we are today as a country and society.

Yuvai Noah Harai’s “Sapiens, a Brief History of Mankind,” had promise, a best-seller, a provocative overview of the development of humankind, focusing on an imaginative narrative of how humans evolved, civilizations developed, empires flourished and disappeared. I found his arguments vague and without deep foundation to truly respect his theories. I did not finish this book.

Memoirs:

Memoirs provided a broad spectrum of subjects, learning about the authors but also the lives they live and the focus of their passions. Sports was the dominant role as the backdrop for several books: “Running Home, a Memoir,” by Katie Arnold (ultrarunner and mother, Arnold’s book delves into her deep, physical grief over her father’s death); “Swimming to Antarctica, Tales of a Long-Distance Swimmer,” by Lynne Cox (the premier cold water swimmer starting at the age of 14 with a record-breaking crossing of the English Channel; dogmatic and persistent in pursuing her dreams and breaking barriers); “The Rise of the Ultra Runners, a Journey to the Edge of Human Endurance,” by Adharanand Finn (a personal journey into the world of ultra-running, trying to understand the “why” of undertaking longer than marathon distance running).

“Nothing to Envy, Ordinary Lives in North Korea,” by Barbara Demick (a journalist who chronicles the lives of six North Koreans who ultimately defected to South Korea, providing a searing view of the poverty, the political lies, the desperation of life in the North). Julie Yip-Williams chronicled her journey after being diagnosed with Stage IV colon cancer at the age of 37 in “The Unwinding of the Miracle, a Memoir of Life, Death and Everything that Comes After.” Michelle Obama’s “Becoming,” was one of this year’s cultural must reads (her reflections on childhood in South Side Chicago to being First Lady of the United States, the struggles, the public spotlight, her unusual opportunities as well as their burdens and benefits). Cheryl Strayed, author “Wild,” her book about hiking the Pacific Crest Trail, was an advice columnist for several years. “Tiny Beautiful Things” contains the actual letters of those seeking advice (“Dear Sugar”) with her heart-felt responses culled from her life experiences.

Social Science/Science:

This combined category reflects the desire to gain insight into areas of personal interest to me, learning the latest science and perspectives. I joined the impact investment committee of a statewide women’s foundation, thus “Good to Great and the Social Sector,” a monograph by Jim Collins (consideration of the difference between operating non-profit and for-profit companies, with focus on impact and operational efficiency) was useful. The opioid epidemic in this country has grave and widespread implications to our nation’s health, survival rates, and economy. “Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors & the Company that Addicted Americans,” by Beth Macy, a journalist, follows six mothers whose children died from overdoses, in tracking this at-first unseen epidemic, the over-prescribing doctors, the dealers-users, the complicity of big pharma, to chronicle in devastating detail this huge scourge on America and its families.

I was personally impacted by the 2002 Women’s Health Initiative that advised that hormone replacement therapy (“HRT”) was detrimental to women in allegedly causing increase in breast cancer, heart disease, and blood clots. The wholesale decision by physicians to accept the study, which was found to be flawed and the results distorted and manipulated, set back women’s health focus years. “Estrogen Matters,” by Bluming and Tavris, is a well-documented investigation into what went wrong. “Why We Sleep, Unlocking the Power of Sleep and Dreams,” by Matthew Walker, explores and uncovers the secret world of sleep: why it is critical to our health, what the brain and mind do while we sleep, the health impact of poor sleep, etc. For a chronic insomniac, his findings are very informative, if not worrisome.

“The Hidden Life of Trees,” by Peter Wohlleben, a strong advocate for trees and forests, lovingly describes their world in anthropomorphic terms while bringing us up-to-date on the latest research into trees, their ability to communicate by a huge complex root system, their longevity, and the difference between natural forests and farmed forests. His lyrical passages fuel my passion to learn as much as I can about these ancient, vital plants.

FICTION:

Classics:

Several women and I formed a short-lived book club this year to delve into classics, books we may have read in high school or college, but wanted to reread as adults. The group only lasted a few months, but it gave me momentum to add more of our literary giants to my every-day reading.

I rediscovered James Baldwin, whose books are timeless, exquisite literary works that challenge thinking about race and sexuality, both taboo subjects in the mid-1950s when he was writing. “Giovanni’s Room” delves into the underworld of Paris, expats and debauchery, homosexuals and leering men and conflicting moral values. “If Beale Street Could Talk” is a story about a young black man falsely accused of ripe, held in solitary confinement in prison, while his young, pregnant wife and family try to clear his name. Both books address universal truths through the focus on individual incidents with tightly-drawn characters.

Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man,” was hailed as “the best Negro novel written” when it was published in 1952. The opus, following a young African American from southern childhood to work decisions in New York City, is powerful, searing in its damnation of the necessity of black Americans to hide their true selves, to be less than what they could be because of society’s prejudices and misperceptions, with the concept/reality of white slave owners always in the shadows of their lives.

“A Room of One’s Own,” is Virginia Wolff’s seminal work on women and fiction writing; the encumbrances of being a woman in a male-dominated society; the notion that having property frees one to be an “incandescent” writer, not beholden to others. I’ve read this book several times over the years and always find new nuggets of truth.

“Tender is the Night,” F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel, whose structure and chronology he struggled with for years, is set in 1920s France. The story is not unfamiliar of that era, expats, wealth, powerful men, pretty women, decadence and decay, the superficiality of friendships.

Books about Race/Immigrants/Refugees:

I’m discovering more non-American born writers (last year, several Nigerian authors’ works were on my list); their perspective, their writing style, their culture, their struggles, and their talent are important to a fuller spectrum of reading.

Likely one of the most poetic, lyrical, yet sad, books I read this year was “On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous,” by Ocean Vuong. (The story is a young Vietnamese refugee’s ode to his mother, but more, the distillation of life caught between the past of Vietnam and the present of Hartford, CT. The mother and son’s relationship is fraught with struggle and physical abuse, but also incredible loyalty. One travels back and forth in time, effortlessly, beautifully, as the layers of the narrator’s life unfolds.)

“Little Fires Everywhere,” by Celeste Ng. (Exploration of family ties, race, what does it mean to be a mother, suburban life, in exquisite narrative and detail. Characters very-well developed, both details of present life and past which presupposes the present. Requires the reader to stretch her understanding of why people do the things they do to loved ones, the hurt, the silences, the misunderstandings. Mia and Pearl, the wanderers, and the Richardsons, the perfect suburban family, mesh and clash. A “can’t put it down” novel, ultimately about love and mothers, sons and daughters.) “The Perfect Nanny,” by Leila Slimani, a Moroccan author, provides another perspective on motherhood. (The story is set in Paris, where couple engage a quiet, competent, devoted woman as nanny for their two children. Over time, the women become co-dependent, with jealousy, resentment, and class/race issues dominating the relationship. A quick read but one that draws reader into the family dynamics, relationships of unequal power, the “handing over” of the duties of motherhood to others, how we think about our own lives.) Isabelle Allende has been a long-time favorite author. “In the Midst of Winter” creates the story of a professor, and two women, one a Chilean professor, the other a Guatemalan immigrant, who are pulled together one wintry weekend in Brooklyn due to accidental circumstances. Their story takes them through a harrowing weekend, learning about each other and the depths they’ll go to help a stranger. Allende uses this arc to discuss race and immigration in America.

I hesitated to read “The Vegetarian,” by Han Kang, Booker International Prize winner, set in modern-day Seoul, South Korea, not certain that I wanted to read of the angst and breaking apart of a family. Ultimately, I found the book thrilling and thought-provoking, delving into places we don’t usually go: family commitments, self-emulation, how can one decide what is best for another person? Finally, “The Refugees,” by Vet Thanh Nguyen, author of “The Sympathizer,” is a collection of short stories, snippets into lives of fictional Vietnamese refugees after arriving in the US after the fall of South Vietnam. Nguyen lightly brings us into the every-day lives of immigrants with compassion and care.

Historical Fiction:

I read several historical fiction books this year; writing in fiction allows the author the freedom to explore true events while sometimes lacking all the facts; often, bringing life to unknown or hidden events.

“The Nickel Boys,” by Colson Whitehead, was heart-breaking. (Based on the Dozier Boys’ Reform School scandal, Whitehead provides a searing narrative of the cruelty of Jim Crow. The Nickel School was calm and lovely on the outside, but darkness resided in the dormitories, the work rooms, the “White House,” where ultimate physical punishment occurred in the middle of the night. Boys were maimed, killed, badly mistreated without remorse. Whitehead’s writing style is spare and emotional, reminding us of hundreds of years of untenable racism in our country. The story moves quickly with a twist ending.) “White Houses,” by Amy Bloom, a fictional account of the relationship between Eleanor Roosevelt and Lorena Hickox, told from Hick’s perspective, was frustrating, wanting to know what was fact and what was conjecture. “The Invention of Wings,” by Sue Monk Kidd, brought to life stories of women abolitionists. (Historical fiction based on the lives of Sarah and Angelina Grimké, likely the earliest women abolitionists in America, as they evolve from members of a Charleston family of slave-owners to breaking free to advocate for women and slaves.)

“Redeployment,” by Phil Klay, tackled the Iraqi war by using fictional narrators. (The author, a Dartmouth graduate and war veterans, digs into the soul of the Marines, the men and women on the ground, their daily experiences, to provide an excellent and precise narrative of the effects, physical and psychological, of that war in particular on our veterans.) And lastly, a unique approach to writing about the Vietnam War, by Denis Johnson, in his “Tree of Smoke, a Novel.” (An existential study of war, particularly the Vietnam War, with twists and turns, orders obeyed and cancelled, uneven chronology (although the chapters are labeled by year), mysteries and secrets, a little like “Apocalypse Now,” and Captain Kurtz, the indiscriminate bombings, the unreality of day to day life, the misunderstandings between leaders in US and military on the ground in Vietnam. The novel is long, the characters sometimes confusing (and confused), but the novel brings you into the explosive and uncertain world of war with the discomfort of being in an unreal reality.)

A jumble of books at a used book store sometimes looks like my brain trying to assimilate my books.

Miscellaneous:

The following is a less-precise list of the “catch-all” fiction works I read this year. Some books were by favorite authors, others were book prize winners (although, to me, that doesn’t always indicate excellent stories), while still others were recommended by friends or family; there are a few in the loose category of “magical realism,” sometimes a fascinating read, other times too imaginary for my tastes.

Haruki Murakami is a brilliant writer, edging into surrealism at times, but always a thoughtful read. “Men without Women,” are short stories about men who happen to live without women in their lives, maybe because of divorce, death, professional commitments. Each story is unique, non-linear, mind-binding (e.g., Kafka’s Gregor Samsa), puzzling, some romantic, others whimsical. In typical Murakami style, his narratives capture the reader’s attention with simple sentences yet complex emotions. Murakami’s “Killing Commendatore,” was published in Japan in two volumes, translated into one volume in English. An unnamed protagonist, artist, separated from his wife, is offered retreat in mountains to spend some time. Staying in the home of a famous Japanese artist, now with Alzheimer’s, the artist encounters strange happenings, a curious wealthy neighbor, a hidden work of art, “Killing Commendatore,” unusual stories and sounds. Part metaphor and magical realism, Murikama creates tension from the various characters, compelling the reader forward to see what ties the events together. A tale of loneliness, discovery, self-reflection, hidden secrets, this long novel, while not as tight as previous works, kept me engaged. I plan to read his “1Q84” this coming year.

Similar to Murakami in many respects, “The Buried Giant,” by Kazuo Ishiguro, is a mythical-like tale, set in post-Arthurian Britain, with a mist settled over the land, causing Britons and Saxons to forget, not only the long-ago (battles, killings of innocent women and children, even mundane family events) but also recent memories. Ultimately, this story is about forgetting, forgiveness, and trust in unfamiliar circumstances. Unique with its creatures, the kindness of strangers, betrayal, and the meaning of love, I found this book engaging and thought-provoking.

Continuing on the theme of odd, almost-mythic, circumstances, in “Atmospheric Disturbances,” Rivka Galchen tests the limits of what one knows or strongly believes to be true against the reality of love and relationships. Unusual narrative, delving into how much one can trust another, what is love, how well do we know others, this novel was difficult, to me, to parse and fall into the story.)

I first read “The Reader,” by Bernard Schlink, many years ago. Set within the story of a young boy’s affair with an older German woman, Schlink explores individual responsibility, the morality of the crimes of the Nazis, and the generational distancing of post-WWII children from their parents. Beautifully written with unanswerable questions about accountability and responsibility, the author develops two characters who are both flawed and human.

Another favorite author, Ann Patchett (her “Bel Canto” was magical; “This is the Story of a Happy Marriage” charming short stories), writes of the tight bonds between a brother and sister in “The Dutch House.” Is it a fairy tale, the mother disappearing, the father remarrying a younger woman with two young girls, the father’s death, the siblings kicked out of their own home, the pull of the Dutch House even as the siblings grow up? Well-developed characters with personal flaws and uneven memories, the story weaves between past and present.

To complement “The Hidden Life of Trees,” Richard Power’s “The Overstory,” is a powerful story of and about trees. This almost-fable-like novel creates an entirely different world than what we humans are generally aware. With millions of years of history, trees grow and procreate, inhabit the earth, benefitting the at-large ecosystem in ways both microscopic and huge. Powers puts trees front and center as the protagonists of his novel, with nine human characters interspersed throughout the book, activists, learners, dreamers, would-be saviors, accidental environmentalists. The literature is rich, the depth of knowledge about the world of trees amazing, the learnings critical. “Giving trees” is an apt description of these ancient creatures and how they so richly created this place we call earth.

I read several other fictional works this year, including the “History of Wolves,” by Emily Fridlund (complicated story line that includes secrets, misunderstandings, a teenager’s perceptions and loneliness, her outlier status at school and at home, combining to create a compelling, emotional, but unresolved study of humans.) Emma Donaghue, the author of “The Room,” (made into movie) explores the relationship between an elderly man and his eleven-year old nephew in “Akin.” While first fighting their kinship, they slowly discover the ties of family and shared history and what tolerance means.

The “to-be-read” shelf (and Kindle) books constantly remind me of what a rich world reading can be. I’ll never be able to read all those I want to read and find myself comfortable not finishing a book that doesn’t meet my expectations. I delight in learning of others’ favorite books and exploring the magical worlds of words that many are able to create.

Room for 2020 books!