We arrived mid-afternoon at Bodhi Khaya Nature Retreat, an eco-sanctuary nestled in a valley beneath the Overstrand Mountains southeast of Cape Town. The drive was an adventure in itself: A missed turn on the narrow road necessitated a very careful U-turn by our bus driver; an overhanging branch required one of the retreat’s staff to shimmy up a tree, machete in hand, chopping the errant tree limbs; finally, the small white buildings of the retreat in sight, the bus driver gingerly maneuvered the ponderous bus over muddy, soft ground. I was immediately awed by the scenery and the gentle warmth of the air. Soon, though, I was quickly escorted to the tiny room that would be my home for the next few days. Staff warned us to lock the doors and close the windows when we were not there –the ever-present baboons could easily get inside. But what if we were inside and they made it through the windows? What were we supposed to do then?

Bodhi Khaya grounds

Bodhi Khaya is unique, located in the fynbos ecoregion of South Africa, an area of Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub biome. Fynbos is known for its exceptional degree of biodiversity and endemism, consisting of about 80% (8,500 fynbos) species of the Cape floral kingdom, where nearly 6,000 of them are endemic. [Wikipedia] The retreat is set among thousand-year-old Milkwood forests; every size, shape, and color imaginable of protea flowers; birdsong from early morning until darkest night; rugged, rocky mountains shielding the back of the valley with wide open skies as we looked toward Walker Bay; and the fresh smells of spring in South Africa. Our retreat’s caretakers easily display their profound sense of place, of conserving the ecosystem, of cooperating with neighbors to set aside and plant thousands of trees to ensure the survival of the flora and fauna of this magical valley.

Climbing a tree to machete a limb that was blocking the entrance to the retreat

Before the trip, I’d re-read “The Unbearable Lightness of Being,” Milan Kundera’s 1984 novel of love and politics in communist-run Czechoslovakia between 1968 and the early 1980s. His premise is that our lives are unbearably light, having no weight, not able to be endured, because our existence is fleeting, coincidental, and non-repeatable. One weekend, though, Tomas, one of the protagonists, experiences a “sweet lightness of being.” He is unencumbered, without obligations or commitments, free. The flame lasts a weekend, opening Tomas to a fresh understanding of himself, to new ideas, to changed expectations of his relationship with others, to a lightness completely opposite the normal weight of his life. Those words have stayed with me over the many years between my readings of this book, a guide star, a phrase that lifts me above my ordinariness.

I’ve experienced this lightness on rare occasions: being with a particular friend; sometimes alone in nature; while running or swimming, the physicality of my movement smooth, flowing, without effort. During these times, I feel no barriers, no judgment, no pre-conceived notions of who I am, what I can say, what is expected. Could being in this ancient country, with my only obligation to be present among the wildness and vastness that is South Africa, spark this sweet lightness, make it more accessible, incorporate it with intention into my daily life? This serene and peaceful valley seemed the ideal place—and time—to try.

View of Cape Town from iconic Table Mountain

We were primed for the retreat after exploring Cape Town and its environs for three days. I was bone tired after almost 24-hours of travel, yet quickly the breezes that flowed from Antarctica to the tip of the African continent caressed my body and awakened all my senses. The chaos and deep rhythm of Cape Town, the light of the magnetic blue sky and the stark steely ocean, alternating between deep blue and foaming white, reflecting one against the other, caught my attention.

Immigrants near Cape Town city center

Africa is a place of contradictions, unparalleled beauty and extreme poverty, the birth place of civilization and the ugliness of inequality and inequity, the brilliance of color and the vastness of brown plains. I felt the turmoil of this place within me as we witnessed the poverty, saddened by immigrants huddled beside city streets with only paper coverings against the weather, no water, no sewer, little food. I experienced moments of complete joy listening to the songs of soaring birds, watching para-gliders float gently in airstreams in the crystalline sky, inhaling the flavors of spring blossoms, and hearing the joyous laughter of little children.

The colors of the city were divine: the pure white colonial Dutch-style houses; the brightly colored pastel homes in Bo-Kaap (formerly a neighborhood for newly -freed enslaved, it is the oldest surviving residential neighborhood in Cape Town near Signal Hill); the windswept top of Table Mountain, covered with orange moss, yellow-flowered ice plants, greyish-green grasses, and the flitting blues of young children in their school uniforms; the glistening brownish-grey magnificent trees, the neon-green ferns, and the millennia-old plants of every hue in the Kirstenbosch Botanical Gardens; color surrounded me at every step. We were bombarded by smells: barbequed meat cooked over charcoal fires out-of-doors; salty air and ripe seaweed near the tide pools; sweet Jasmine wound around lattices on our guest house; and the rich aroma of morning coffee wafting into my room as I awoke to another day of new experiences.

Bo-kaap neighborhood in Cape Town

The sounds, especially the beat of African drums and the rich singing resonated within me, the pull of millennia visibly relaxing me, a smile spreading across my face, a swaying motion wanting to express itself; the cacophony of people walking the city streets, horns honking, food hawkers screaming their wares, police sirens blaring, children laughing at some absurdity; the crashing waves, receding then moving forward with such force that the waves blasted against the sea wall, sending people scrambling to drier land; all together confirmed the foreignness of this place but also its essential nature.

Taste, too, was all around: the earthy freshness of berries; the spicy delicacies of Indian food; the 14-course meal at our “African Experience,” with unknown vegetables, sauces, and a variety of wild animals, combined for a feast far beyond my typical standard fare; the ubiquitous biltong (South African dried meats), eaten as a snack on our longer bus rides; and soups, so many kinds, orange-squash soup, cauliflower soup, broccoli soup, lemon-pumpkin soup, each amazing and delightful.

Exquisite African dress (from the African Experience)

The startling serenity of Bodhi Khaya was a balm after Cape Town. Within an hour of our arrival, we were sitting on the floor of the meditation/yoga room where Merle, our facilitator, greeted us. She set the stage for three days of meditation, reflection, and writing. We would meet for several two-hour sessions a day, with some nature walks scattered in between sessions, ending with a day of silence and after-dinner fire circle. The goal was to take advantage of the unique and diverse nature surrounding us to (re)discover our essential beings. I’d thought the days were be focused on creative writing, a way to re-ignite my love of the written word. This unexpected pivot was a little alarming for this introvert but the challenge might be an opportunity.

“Who am I?” “Why am I in South Africa?” “What are my intentions?” “What is happening to me right now?” “What is my gift, my original medicine, my contribution to society?” The questions were difficult and searching. Diving immediately into meditation exercises forced me to evaluate this journey: why I’d chosen to come to the “dark continent,” without spouse or children, knowing I might be uncomfortable traveling almost-solo, but even more, knowing I might be uncomfortable opening myself up to others, perhaps discovering things about myself that I’d kept buried or didn’t even know where a part of me. I am an introvert, needing quiet, alone time to recharge, to absorb the day, to become social. I suppose some of my pre-trip anxiety was how I would sleep, how I would protect “me” time, how I’d relate to the other travelers only a few of whom I knew from my Pilates studio (the owner is South African and curated this journey). Stripped of the noise and interruptions of daily life, could I find lightness in this venerable country?

The ubiquitous Protea flower, glorious!

We wrote brief, bullet point responses in our private journals as each question was posed; the goal, to eventually integrate the “in the moment” thoughts into a cohesive reflection of ourselves; more importantly, of our place in the world. It’s easy to write who I am in relationship to others: mother, wife, grandmother, sister, aunt, friend, colleague, attorney, philanthropist, runner. It’s difficult to define who I am without these precepts, the external markers, the self we give to the outside world because it’s expected of us. Would I recognize the stripped-down version of me? Would others? An on-going process for so many of us.

One morning, between writing exercises, I walked barefoot in the grass (when had I last done that? something I so enjoyed as a child, the blades tickling my toes, the damp dirt sticking to my feet, my whole body grounded) to sit by a gnarled, grizzled tree, its bottle-brush red flowers hidden among the scarred limbs. I stared at the tree, losing myself in its beauty, emptying my mind of the morning’s tasks and the planned afternoon activities, and breathed. Trees communicate through an intricate web of roots, fungi, plants, and soil, a community yet each one also an individual–we humans can be that way, too, alone but with others. The stillness mesmerized me; a light breeze ruffled the blades of grass; the plants moved in synchronization; the birds chirped and hawked to one another; the weight of whatever was on my mind lifted, allowing me to sense this place whole-heartedly. Maybe this is my sweet lightness, intervals of time without time, forgetting the world for a few moments, listening to what is around me, not what is inside me.

“My tree”

The pull of my hometown in southeastern Washington gives me a similar sense of place: I return time and again to refresh, to reflect on my childhood, my parents, and my current life, to revel in the green valley against the rolling hills of the Blue Mountains. Almost like a salmon swimming upstream by the scent of its birthplace, these places call to me. It is probably when I am most “light,” not weighted down by my obligations, my concerns, my fears, my disappointments. “Place” is critical to me, to my comfort level, to my ease among the world. Finding those places is a profound search that I immediately recognize when they fill my heart.

Spring wheat in the Walla Walla Valley with Blue Mountains to the east, my birth home

There is an African proverb: “Home is not where we live. Home is where we belong.” The literal Nigerian translation, from where the proverb originates, is: “Home is where life is found in all its fullness.” This is such a lovely, descriptive definition, encapsulating for me some of the lightness that I seek. Whether the ancient grounds of Africa or the once-Indigenous lands of my original home in southeastern Washington State, I catch fleeting moments of that lightness for which I am searching. The question of why I am in South Africa, at this time, with this group of people, at this serene nature retreat, may be answered by its unique place, its planting season of renewal, its isolation from the noisy world. I am unencumbered, able to run on dirt roads where baboons frolic, walk on narrow trails among centuries’ old trees, sit around a fire learning to beat an African drum with the southern stars brilliantly sparkling in the dark night sky. For now, this may be enough.

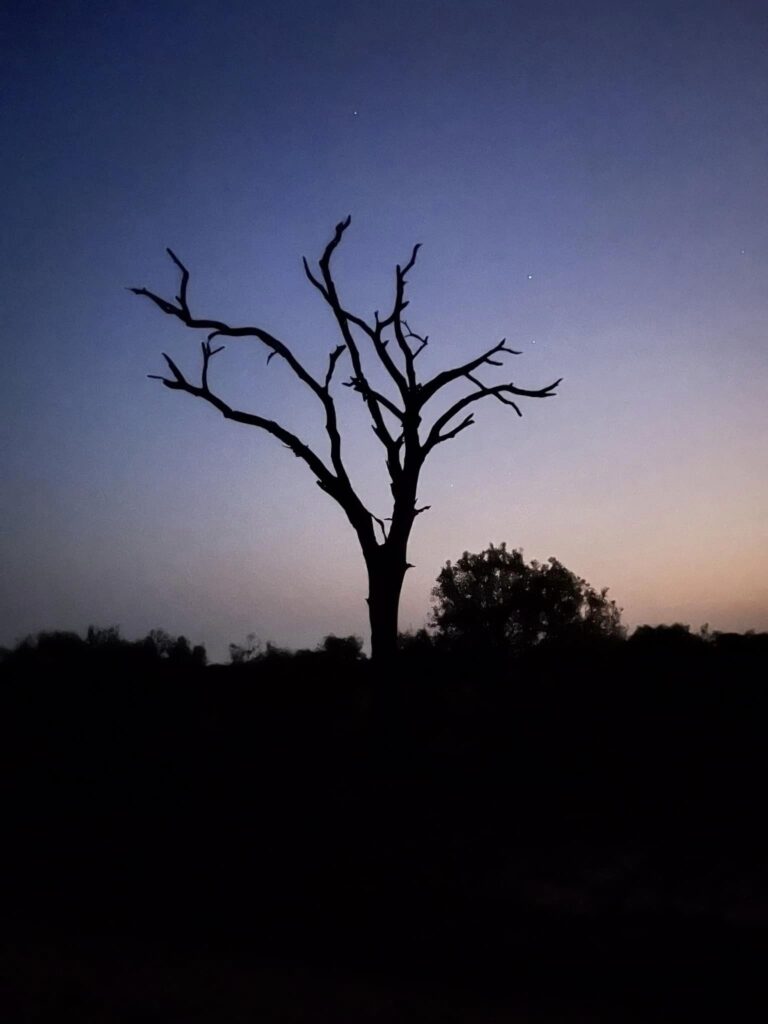

South African sky

Beautifully written, descriptive and emotive! Kudos Pat for capturing the essence of the journey both within and out!

Thanks! This was more difficult to write than the mere observations but wanted to try.

Such beautiful detail. Thank you!