What does a dedicated runner do when she cannot run, felled by injuries, inclement weather, or travel? Or perhaps she wants to cultivate cross training activities, to enhance her running but also to work other muscles and strengthen connective tissue? Maybe she wants to shake up her daily routine while maintaining aerobic capacity, muscle strength, power and endurance? Or maybe she just wants to reclaim the muscle memory of childhood sports that also complement her current physical and mental training?

Old San Juan (Fort) and Caribbean Ocean

“You will have to change from greyhound to porpoise.” I was a bit puzzled by my friend’s note, after my physical therapist said, “No running,” at least until the biting hamstring pain resolved, maybe as long as several months. Upon reflection, however, I realized that I have often been described in terms of animals. Anthropomorphism is defined in the Merriam-Webster Dictionary as an interpretation of what is not human or personal in terms of human or personal characteristics. I was saddened that my greyhound (my running self) was to be held in abeyance, yet by encouraging my porpoise (my swimming persona), he reminded to seek that long-ago love as a backup to my favorite activity.

I considered my history with anthropomorphism, wanting to bolster my spirits as I sought a way to address the intentional putting aside of running. Perhaps I would find it in one of those animals.

Windsor, CA 10k (2015)

Porpoises are one of the fastest cetaceans (marine animals such as whales, dolphins and porpoises), with speeds of up to 34 mph. They generally live in shallow coastal waters. Smaller than dolphins, they can be more aggressive and do not adapt to living in captivity. Female porpoises often give birth each year, with an eleven-month gestation period. Can you imagine, being pregnant almost all year every year?

Greyhounds are a gentle and intelligent breed whose combination of long, powerful legs, deep chest, flexible spine and slim build allows them to reach average race speeds in excess of 40 mph. They have short careers as racers; due in large part to the efforts of rescue shelters, they are becoming more common as family pets. Maybe that will be my fate?

Roadrunners are long-legged, strong-footed ground cuckoos, living in the southwestern part of the United States. Roadrunners can run as fast as 20 mph. They are also mascots for various sports teams, imagery to imbue the athletes with visions of speed and winning. One of my favorite pieces of jewelry is a copper roadrunner, a physical reminder of this endearing term.

Rabbits are small mammals, with large, powerful hind legs. Jackrabbits hop quickly and at long distances, perhaps akin to track and field athletes who specialize in the long jump or triple jump. “Rabbits” also refer to pacers used in middle-to-long distance running to ensure a fast pace, often dropping out of the race at some designated point (except when an occasional rabbit decides to run for the win!).

During my junior high and high school years, I felt a misfit, chubby, nerdy, without physical grace. I discovered the YMCA as a place of consolation, of acceptance. I spent hundreds of hours with some of the other brainy girls as part of a synchronized swimming group (we called it water ballet back then; arguably more dance and art than athletics, it was not then an official summer Olympics Games’ event). We performed balletic moves to jazzy music; choreographed underwater dances; sewed sparkly sequins on our lacy costumes; participated in competitions. I was a mermaid, a sea horse, even a water baby as the silky water embraced me. I swam with grace and precision while my hair and skin were permanently infused with the faint perfume of chlorine. I could have floated forever.

San Diego boardwalk (with broken arm)

I was nicknamed the “roadrunner” by friends when we backpacked in the Trinity Alps. Located in Northern California, these granite peaks are glorious, isolated, accessed by little used, poorly maintained trails. The 55 alpine lakes are tucked beneath granite walls of the Red Trinities, the White Trinities and the Green Trinities. We often hiked to Adams Lake, a tiny, crystal clear, cold lake off the dirt road out of Weaverville, California, a town once known for its Gold Mines and Chinese workers. I typically led the group, not because I was the natural trail-leader (that was Tom, who hiked to the lake as a child with his uncle) or map interpreter (the U.S. Geological Maps were critical for the hidden passages), but simply because I liked to move—quickly. I couldn’t abide going slowly, that is, until the day a baby bear stumbled across the steep shadowed trail just in front of me. Backwoods knowledge assured me that his or her mother would be close at hand. I decided that being in the middle of the group of hikers was smart. I curtailed my enthusiasm in the name of safety. Still, once we made camp, while the men fished, I scampered up and down the peaks, maybe a gazelle, free—but always watching for danger.

Big Steps (Manitou Incline, Manitou Springs, CO)

A few years later, I started my life-long love affair with distance running. The activity began as the twin-antidote, along with swimming, to studying for the California bar examination. It morphed into so much more, as my form improved, my pace quickened, my running economy developed. In Humboldt County, where I lived for six years after finishing law school, I met wonderful people while running at the local track and loping along country roads. Soon these people became my best friends, confidants, and substitute family. We logged ten, twelve, fourteen miles at a time. I became a trainer, or “rabbit,” for a few of them who were training for the Avenue of the Giants marathon, a 26.2-mile course that weaves in and out of the towering redwoods and fern forests of the southern part of the county. Running was at the essence of our friendships, the tool to allow us to develop other passions and reasons to be together.

I suppose during these years I might also have been considered a “greyhound,” as my silhouette changed from bulky pubescent teen-ager to slender, long-limbed young woman in the shadows of the sun as I ran the hills and trails above town. I felt a freedom unlike any other in my life at that time. Running was my savior and my daily elixir. Those feelings lingered, even through the many years of being a mother, wife and crazily busy attorney, when running took a backseat to daily life.

Lap pool near our house

My friend is wise, a man I’ve known since we were in kindergarten with Ms. Rose as our teacher. He’s also suffered injuries at various times, curtailing his skiing, race car driving, and hunting. We’ve gone our separate ways only to reconnect occasionally by telephone or email or, in more sad times, at one of our respective parent’s funeral services. My friend’s admonishment to me was really a favor: find my other strengths. Running isn’t necessarily gone forever, just on hiatus.

So I found my way back to swimming, not synchronized swimming, but lap swimming. I took a few lessons to relearn breathing, to sway slightly, to glide more easily with less disruption through the water. I still need to learn the elusive kick-turn, but it will come. And one day, swimming became poetry, different than running, but unique in and of itself.

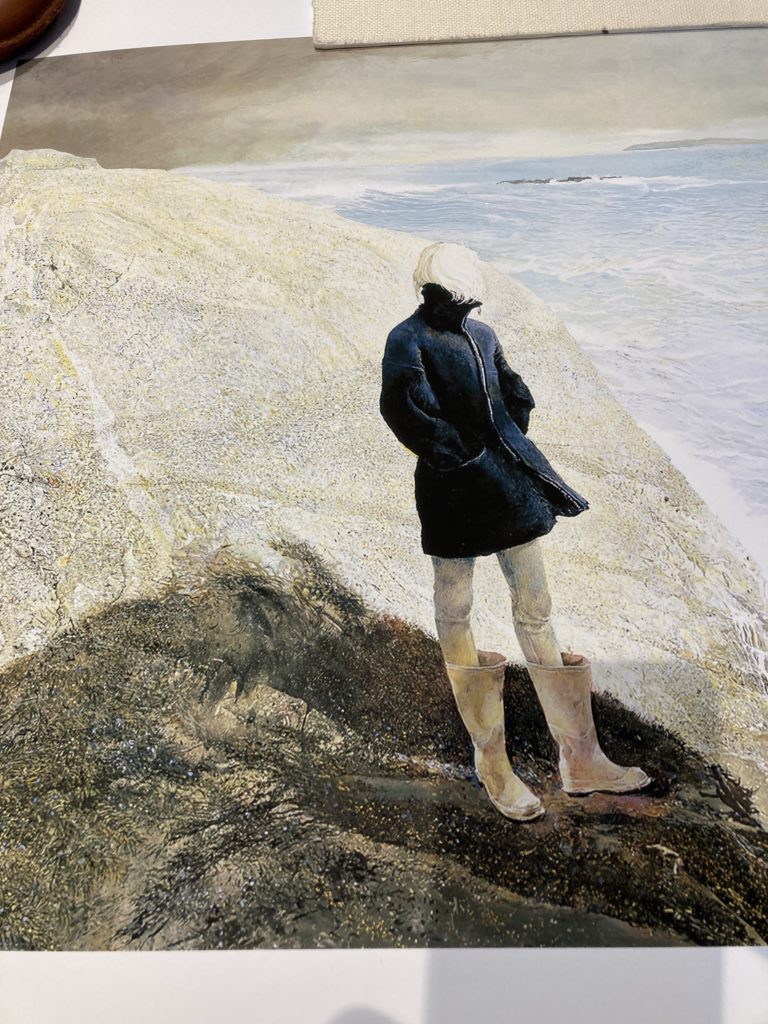

Painting: Jamie Wyett

I imagine porpoises swimming gracefully in the Pacific Ocean, impervious to outside worries. Once I slip into the pool, the laps glide by one after another. Bubbles trace the movement of my lingering fingers deep beneath my arm strokes, like duckling in a row behind their confident mother. I prefer the middle laps of the swim: my body sways slightly side to side and every third stroke my head turns, to the right, gathering breath, letting it out, then another three strokes and the same movement, this time to the left. The slight rumbling of my outlet air, the echoes of water slapping the pool’s edges, the occasional splash from a fellow swimmer are the only sounds to break this reverie. The rhythmic motion lulls me into believing we may once have been a more integral part of the ocean, the lakes and the rivers, the water our long-ago home. As I close in on the mile, I am forced to concentrate, my arms heavy, the kick of my legs less vigorous, and my breathing more labored. Yet I finish, refreshed, tired, and ready to start the work of the day. Running will still be there waiting for me, once my legs strengthen. Until then, the water is my physical world.